In 1982, Ridley Scott made Blade Runner – a sci-fi noir that struggled financially when it was released, but has since become a genre classic.

Few movies in the history of cinema have made the kind of visual impression left by Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. Over four decades on, the reach of his third film remains near unparalleled. If Alien inspired legions of storytellers to come, 1982’s Blade Runner established a template for futuristic neo-noir most creatives have since adhered to.

Scott’s journey into science fiction, via the hugely successful Alien, was fuelled by Star Wars, given the director was set to follow up his debut The Duellists with a version of ‘Tristan and Isolde’, the 12th century chivalric medieval romance (a logical fit following that earlier period film, it would have seemed). By the early 1980s, Scott was in an entirely different place, certainly in terms of his career. His star was in ascendance.

As it was with Alien, his route to directing Blade Runner was circuitous, and part of a longer history. An adaptation of sci-fi writer Philip K Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep?, it had been mooted as a feature since the end of the 1960s, with Martin Scorsese circling it after making his first feature, Who’s That Knocking At My Door?. It was optioned by Herb Jaffe in the early 1970s, but the screenplay by his son Robert was rejected by the exacting Dick.

Then came Hampton Fancher, a screenwriter who in 1977 developed a draft that was optioned by producer Michael Deeley, beginning the journey toward what would become Blade Runner. Incidentally, what now seems like the perfect title for a sci-fi movie had no relation to Dick’s book. Aware, perhaps, that Dick’s title wouldn’t make sense to mass audiences, when Scott entered the picture he enjoyed Fancher’s reference of a treatment by another counterculture great, William S Burroughs, for Alan E. Nourse’s novel ‘The Bladerunner’ (a story about underground medical services smuggling). Deeley was asked to secure the rights and the rest is history.

Blade Runner came to Scott during a difficult point in his life. His elder brother Frank had passed away of skin cancer in 1980 – just at the point Scott was circling an adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune with producer Dino de Laurentiis, later made by David Lynch in 1984 (Scott’s younger brother, Tony, later died under equally tragic circumstances in 2012). Scott seems the perfect fit for the scope and thematic ideas in Dune, and while he had a screenwriter working on it, de Laurentiis’ plans for shooting put Scott off, as he later told Total Film:

Dino had got me into it and we said, ‘We did a script, and the script is pretty fucking good.’ Then Dino said, ‘It’s expensive, we’re going to have to make it in Mexico.’ I said, ‘What!’ He said, ‘Mexico.’ I said, ‘Really?’ So he sent me to Mexico City. And with the greatest respect to Mexico City, in those days [it was] pretty pongy. I didn’t love it. I went to the studio in Mexico City where the floors were earth floors in the studio. I said, ‘Nah, Dino, I don’t want to make this a hardship.’

Scott had rejected an approach to direct a version of Do Androids Dream… before Deeley came along; when Deeley managed to convince him that it was the right project, Scott sought changes to Fancher’s script. He brought in David Peoples to write another draft, though Fancher did return to provide later drafts, and indeed would go on and pen the Denis Villeneuve sequel, Blade Runner 2049, which Scott later lamented not making himself. Villeneuve would, of course, later go on to make what for many is the definitive cinematic adaptation of Dune. It all connects.

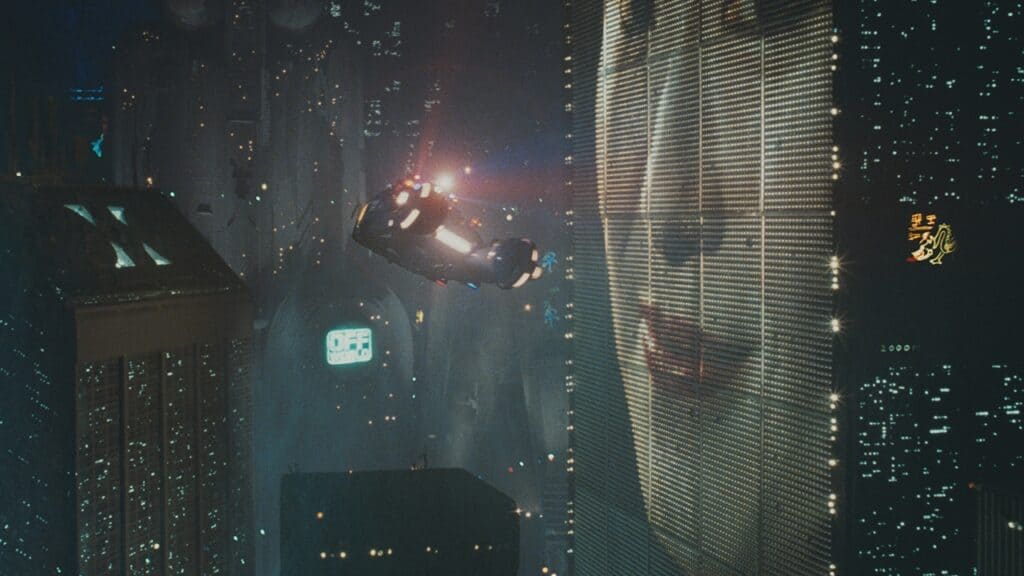

Blade Runner feels like a natural extension of Scott’s talents in the wake of Alien, where he took the bones of a script and crafted a distinct visual world that has, in subsequent decades, been endlessly imitated, and helped develop a visual language for dystopian sci-fi futures. He does the same in adapting Dick’s story, which is about ‘blade runner’ Rick Deckard (as played by Harrison Ford) whose mission is to hunt down a cadre of renegade ‘replicants’ – outlawed machines designed to look “more human than human”. It all takes place in a Los Angeles of the now historical 2019 filled with neon colour and near future inventions, all brought to life through Scott and his collaborators’ spectacular production design. The film looked like nothing else before it.

As was the case with Alien, it stemmed in part from Scott’s early days developing his skills as an artist, as he told The Telegraph:

After grammar school, art school was like the goddamn door opening – seven years in constant study of form and light. And then, I see things in a certain way. It probably goes back to industrial England, and, a lot of people would say, that’s why you get Blade Runner. There were steelworks adjacent to West Hartlepool, so every day I’d be going through them, and thinking they’re kind of magnificent, beautiful, winter or summer, and the darker and more ominous it got, the more interesting it got.

This, for me, is where Blade Runner shines. The contrast between light and dark. The use of shadow. The fusion of electricity and nature, often in the form of driving rain. Scott and his production designer Lawrence G Pauli, plus his special effects supervisor Douglas Trumbull (who had been a key figure on Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, one of the major inspirations for Scott), combine these juxtapositions as they build a world not dissimilar from that of Alien. These are Easter eggs in later Alien films that suggest Blade Runner and it’s sinister Tyrell Corporation might exist in the same narrative universe, and you can believe it.

These are both worlds constructed on the masses being controlled by entities with godlike aspirations, as the Alien films when Scott returns to them will later explore in more depth. Blade Runner deals with the concept of the creation rising up to destroy god once it becomes self-aware of its own mortality. Roy Batty (menacingly yet sensitively portrayed by Rutger Hauer) is a manifestation of this. We can see it when he confronts his maker, Dr Eldon Tyrell (Joe Turkel), who claims “you were made as well as we could make you”, and Batty replies, “but not to last.” Tyrell’s reward for this? His creation pushes out his eyes and leaves him in a bloody heap on the floor.

Technology and biology, again, as in Alien, morphing to create a threat to humanity and the natural order. That is what Deckard is recruited to put down, with Fancher and Peoples’ drafts establishing him as a cop figure within a fairly traditional 1940s noir narrative. Deckard has to traverse the cold, teeming city looking for clues. He has the requisite femme fatale in Rachel (Sean Young), who may or may not herself be a replicant. Tyrell exists as the shadowy paymaster behind events. Batty the rogue agent. Everything is well placed in that regard, backed by Vangelis’ unique, jazzy and haunting score. You understand these tropes as an audience while watching Blade Runner place them inside a new context, using the story to pose huge questions about the nature of humanity.

By all accounts, the shoot was not a happy one, fraught with issues. Scott discussed this with Total Film:

I had horrendous partners. Financial guys, who were killing me every day. I’d been very successful in the running of a company, and I knew I was making something very, very special. So I would never take no for an answer. But they didn’t understand what they had. You shoot it, and you edit it, and you mix it. And by the time you’re halfway through, everyone’s saying it’s too slow. You’ve got to learn, as a director, you can’t listen to anybody.

Though they have since reconciled any differences, Scott also struggled with Ford’s temperament, the actor having nabbed the role from numerous other candidates (including Robert Mitchum, who it was written for initially) because he was hot property following Star Wars and Raiders Of The Lost Ark. It was perhaps the clash of two driven men who didn’t suffer fools gladly. Ford once discussed the experience in relation to the infamous voiceovers that bookended the film:

When we started shooting it had been tacitly agreed that the version of the film that we had agreed upon was the version without voiceover narration. It was a fucking nightmare. I thought that the film had worked without the narration. But now I was stuck re-creating that narration. And I was obliged to do the voiceovers for people that did not represent the director’s interests.

This became a big bone of contention for decades with Blade Runner, in terms of which was the definitive version. Scott put the issue to bed in 2007 with the release of The Final Cut, his own ‘directors cut’ in essence, with several tweaked shots and a 4K rendering which he described as the closest approximation to what he wanted Blade Runner to be. As with the earlier Director’s Cut, released in 1992, The Final Cut eliminated Deckard’s voiceover (a move that no doubt pleased Ford) and also cut out an extended climactic sequence with Deckard and Rachel heading off into the countryside. The latter was cut together using leftover shots from Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, and was added to the original theatrical cut at the behest of the studio. There is no question – The Final Cut is the best rendition of the film by far.

It took me too long to see it, and this is where I need to make a late in the day confession – I’ve never really liked Blade Runner. It’s an opinion that has seen some friends and colleagues threaten to remove my film writer card, but nonetheless I can never quite get to any kind of adoration for it, despite multiple rewatches. Do I respect it? Hugely. I completely appreciate the sizeable impact it has made on cinema, artistically, since it was released. For many, it’s highly ranked in Scott’s evolving oeuvre. Everyone has a film or two they just can’t get behind. Blade Runner is one of mine. I can never completely enjoy it.

There’s no question of how important it was to Scott and his career, however. Eric Cohn for Indiewire described it in 2017 this way: “Outside Star Wars, no sci-fi universe has been etched into cinematic consciousness more thoroughly than Blade Runner.”

Scott himself has described it as his “most complete and personal film,” and strongly suggests the reason was his late brother Frank, who Scott would visit when he was terminally ill, and whose loss left a trauma he needed to work through. So much of Blade Runner feels about endings, about the promise of life slipping away.

Batty’s final words echo this feeling: “I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhauser gate. All those moments will be lost in time… like tears in rain…”

Yet in the deleted final narration, Deckard suggests he loved life more than ever in these final moments. I suspect Scott struggled with this notion as he was not, as a filmmaker and a human being, in that space when he made Blade Runner. He was questioning what life is, why we’re here, and noting that our time is short.

As we’ll increasingly find, these are questions and sentiments that have never really left his work.