Starbucks, Amazon, WeWork, McDonalds – all brands seen in David Fincher movies, from Fight Club to The Killer. We take a look at what it all means.

“There are 1,500 McDonald’s in France. A good enough place to grab ten grams of protein for a euro…”

Having been a feature filmmaker for over 30 years by now, David Fincher knows a thing or two about getting a movie made in a profit-driven industry. A successful commercials director before he broke through with Alien 3, Fincher also knows about selling a product through a single, arresting image. Which is why, when the director blows up a shop front filled with Apple products or shows Brad Pitt and Edward Norton smashing up a VW Beetle (1998 model) in Fight Club, you can be sure there’s more going on than mere corporate-backed product placement.

In Fincher’s most recent film, The Killer, Michael Fassbender’s nameless hired assassin prowls around a jungle of corporations and brands. He flies with Air France during his globe-trotting escapades. He drinks Starbucks coffee (a possible throwback to Fight Club – more on that later), eats at McDonalds, and buys gadgets from Amazon Prime. He’s a distinctly modern kind of assassin.

Product placement has long been a part of movie-making, not least because getting money from advertisers allows studios to offset the increasingly hideous costs of making those movies. In many instances, the product placement in David Fincher movies is just that – product placement. It’s almost certainly why Rooney Mara can be repeatedly seen using a MacBook Pro in The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, or Rosamund Pike holds a bottle of Leffe with the label on full display in Gone Girl.

The choice of a new generation

At other times, though, product placement is integral to Fincher’s plots. Fight Club, adapted from Chuck Palahniuk’s novel, is a counterculture horror thriller that takes place in a contemporary reality of ubiquitous advertising and logos. Edward Norton’s disaffected office worker talks gloomily about unknown worlds conquered and branded by corporations (“Planet Starbucks…”) and lives in an apartment packed with furniture and ephemera from a thinly-veiled Ikea analogue.

Fight Club’s partly about rebelling against societal norms and rejecting capitalism, and David Fincher is keenly aware of the irony that a film with anti-capitalist themes is being backed by a major studio like 20th Century Fox. Rather than try to gloss over this potentially awkward paradox, Fincher plays with it – companies like VW and Apple and Mountain Dew evidently paid to have their branding included in the movie, and yet those brands are repeatedly shown being smashed with cricket bats or blown up with improvised explosives. In one scene, shop clerk Raymond K Hessel (Joon Kim) is shown cowering in front of a pair of Mountain Dew and Pepsi vending machines.

In Fight Club's DVD commentary track, Pitt even points out that whenever there’s product placement in the movie there’s often “violence or someone crying” at the same time. Fincher and his collaborators somehow got away with bending the studio-mandated need for product placement to suit the film’s mischievous, anarchic themes. Years later, Fincher caught the internet’s imagination when he invited viewers to spot the plethora of Starbuck’s coffee cups he supposedly hid in every scene.

Move fast and break things

As Fincher has moved from genre to genre in the years since he made Fight Club in 1999, some of its themes seem to have clung to the director’s bones. The Social Network (2010) is about the creation myth of not just a world-dominating social media platform, but also a brand – Facebook (“Drop the ‘The’ – it sounds cleaner”).

Fincher and screenwriter Aaron Sorkin’s portrait of the platform’s founder Mark Zuckerberg is of a somewhat lonely figure whose arrogance and impatience leaves him isolated from his peers – ironic, given that he creates a product that allows billions of people to connect over the web.

Gone Girl (2014), meanwhile, takes place in the world created by Mark Zuckerberg and other billionaires who forged the modern media landscape. Written by Gillian Flynn from her own novel, Gone Girl is a thriller that’s all about identity and appearances – the appearance of owning the immaculate, middle-class home, the appearance of being the perfect couple and living the perfect life – and how individuals sculpt and shift their identities to fit.

Amy (Rosamund Pike) and Nick (Ben Affleck) have all the outward trappings of the idyllic, all-American life – but behind the facade lies something nasty and even murderous, which Flynn and Fincher slowly lay bare, like peeling apart an onion. Gone Girl is a thriller for the age of social media, of Facebook and Instagram, where the appearance of happiness, likeability and success are paramount. Ultimately, there’s a sense that Fincher rather enjoys Amy and Nick’s fate – on some level, perhaps they deserve each other’s misery.

I’m lovin’ it

The protagonist at the centre of David Fincher’s latest film, The Killer, on the other hand, is the polar opposite to the couple in Gone Girl. Played with lizard-like calm by Michael Fassbender, is an individualist – he’s the antithesis of the social media-conscious modern citizen who wants to be seen and to fit in. Rather, he wants to be as anonymous as possible in order to exist outside the norms of modern reality, where what you wear and how successful you look is sometimes regarded as important as eating and drinking.

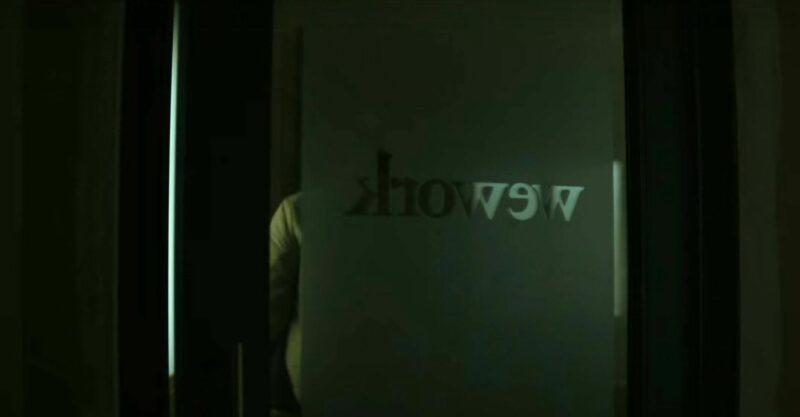

It’s here that Fincher’s use of real-world products and brands again comes into play. Much as Fincher did in Fight Club, Fassbender’s titular killer uses corporations and their products to his own ends. Fincher is careful to point out to us that the killer’s base of operations in Paris is an abandoned office once owned by WeWork – a company valued in the billions only a few years ago, only to dwindle and finally go spectacularly bust in 2023. The killer uses Amazon’s almost instant delivery system to break into buildings. His treatment of a McDonald’s meal is particularly telling: he eats the protein but discards the carb-heavy bun. Take what you want from modern society and leave the rest.

Like Tyler Durden, Mark Zuckerberg, Rooney Mara’s Lizbeth Salander or even Amy Dunn at her most scheming, Fassbender’s killer is another singular character who Fincher evidently admires, despite the darker aspects of his nature. Perhaps it’s because these characters all find their own way of navigating through a world of products, brands, and shallow outward appearances.

The Killer, after all, takes place in a contemporary reality where, on some level, we’re all conscious that big tech companies, perhaps even capitalism itself, is quietly messing with us. It’s a reality where Google tampers with your search queries so it can sell you more stuff. Where Amazon aggressively prohibits its sellers from offering their products more cheaply elsewhere, resulting in inflated prices. Where a dating app like Tinder plays with your emotions in order to keep you hooked. Where Uber will charge you more for a taxi ride because it knows your battery level’s low and you’re desperate to get home.

Work hard. Have fun

Perhaps this is why, even though the protagonist in The Killer is almost certainly a sociopath, Fincher finds him so fascinating. He may be a sociopath, but then we’re surrounded by inescapable corporations and entities that appear to do some pretty sociopathic things themselves. It’s at least satisfying to see the tables turned in some small way – even if it’s as simple as using the husk of a self-evidently unviable business as the base camp for a sniper assassination.

In his murderous, globe-spanning missions, Fassbender’s killer is often shown throwing his phone on the floor and stomping on it until its screen splinters. In theory, he does this to avoid being tracked by government agencies or whoever else might be on his tail. At the same time, the image of a boot stamping on a smartphone could also be viewed as a distinctly modern symbol of rebellion.