Designer Jordan Mechner pioneered motion capture with Karateka and Prince of Persia. He reflects on his games’ making, legacy, and what came afterwards.

When Jordan Mechner was growing up in 1970s New York City, he, like many kids, enjoyed playing the arcade machines that were just emerging at the time. “I used to play the likes of Space Invaders and Breakout, and they became the kind of games that I aspired to make,” he recalls.

After saving up enough money from drawing cartoons to buy an Apple II computer, Mechner set about coding his own version of Asteroids. “But Atari was cracking down on companies selling unauthorised knock-offs of their titles on floppy disks,” Mechner says, “so my game – called Asteroid Blaster – couldn’t be published.”

Undeterred, he spun the project into Deathbounce – “a game like Asteroids, but with brightly coloured bouncing balls” – which he sent to the publisher, Brøderbund. Again, it was rejected, but he received a pivotal call from the publisher’s founder, Doug Carlston.

“He said my game was a little bit last year – kind of 1981,” Mechner laughs. “He also said Brøderbund’s big hit at the time was Choplifter and he encouraged me to check it out, sending a copy in the post and the joysticks to play it. That game just blew me away.”

Choplifter was a side-scrolling action game developed by Dan Gorlin for the Apple II. Assuming the role of a helicopter pilot, players rescued prisoners of war while fending off the enemy. “What I loved was that it told a story, and it wasn’t just racking up points to get a high score,” says Mechner.

“Choplifter was a revelation, because I realised I’d been copying the coin-op format without realising that home computers didn’t have a coin slot, and so games could be different and tell tales with a beginning, middle, and end.”

Developing a technique

Mechner’s entire approach to video games changed in an instant, and he decided he wanted to develop titles with a cinematic quality. As a film student at Yale University, he was influenced by the movies of Japanese director Akira Kurosawa, in particular the epic 1954 drama, Seven Samurai.

“I enjoyed the Samurai mystique of bravely going forward and accepting death as a possibility,” he explains. “I was fascinated and inspired by the spirit of Bushidō which dictated the Samurai way of life, as well as the stylistic simplicity of Japanese landscape prints, such as [Katsushika] Hokusai’s Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji.”

Mechner also enjoyed kung-fu movies, which led to the development of Karateka – a martial arts action game which earned itself a Guinness World Record for being the first video game to make use of motion-capture animation. The technique Mechner used was called rotoscoping, which involves filming real-life movement and tracing over the footage to copy it to a computer.

Karateka was released in 1984, initially for the Apple II computer. There was a remake released for the Xbox 360, Windows, PlayStation 3, and iOS in 2012.

“Karateka was the first time I’d used rotoscoping,” Mechner says. “I used a Super 8 camera to film my karate teacher doing the punches and kicks that would be needed for the game, and I filmed my dad running and climbing onto the hood of a car to simulate climbing up a cliff.”

For Mechner, it was a way of exploring a new medium in a manner that hadn’t been seen since the early days of film. “I was watching early silent films, and I realised how the cinematic language that we take for granted with the close-ups and camera movements had to have been invented,” he says.

“I thought computer games were this new audio-visual medium with a potential that hadn’t really been explored yet, and my eyes were open to the possibilities.”

Frame by frame

Rotoscoping dates back to 1915, when animator Max Fleischer first used it in the silent era series, Out of the Inkwell, which featured a highly realistic moving character, Koko the Clown, posed by Fleischer’s younger brother, Dave.

It was a technique Disney’s animators would use to similarly groundbreaking effect in the studio’s first feature film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, in 1937. “Those animators were tracing onto paper and then onto acetate cells, but the process of replicating the technique for Karateka on the Apple II was a little more complicated,” Mechner explains.

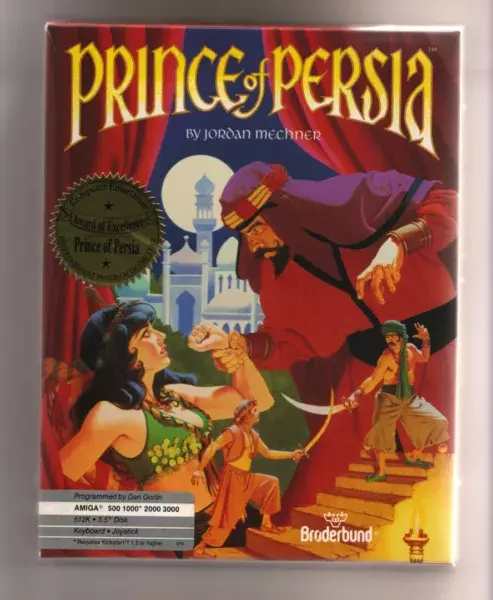

Prince of Persia’s box art captured the game’s cinematic quality.

“I had to trace pixel by pixel, and it was very much a homemade process. “One of the other difficulties was the worry about wasting film. With Super 8, you get just a couple of minutes on the roll, so you’re kind of in a panic because if you wasted 20 seconds of film, you couldn’t just rewind and do another take. You also had to get that film developed, which took time.”

Made in just 48kB of memory, Karateka was a massive hit when it came out on the Commodore 64 in 1984. Buoyed by that success – and having made enough money to pay off his loans from college – Mechner began working on his second game.

An even more ambitious project than Karateka, Prince of Persia took a long four years to develop. Coded in 6502 assembly on the Apple II once more, it too made use of the rotoscoping technique, this time swapping a Super 8 camera for VHS.

“It was a step up, but it was still a very slow, manual, step-by-step process,” says Mechner. “The big advance between 1982 and 1985 was that a company in England called Compu-Tech had created a digitiser card, which you plugged a video camera into. I just needed to create sheets in which each animation frame was clearly silhouetted in white against a black background.”

To create a sheet with eight to twelve frames of animation on it, Mechner would videotape a model wearing white clothes – in this case, his brother Dave again, who would run, jump, and climb, creating the movement that would translate into the character of the Prince.

“I would then put the tape into a VHS player that had a clean freeze-frame and put a 35-millimetre film camera on a tripod in front of the TV screen,” Mechner explains. “The idea was to do a frame advance, take a picture, do another frame advance, take another picture and so on, using every third frame, and then take that roll of film to the photo lab to be developed.

“I’d get back a little stack of photographs, each of which was a frame of video. I’d then paint those photographs with a black marker pen and use white to create a silhouette before taping them all together onto a sheet.”

Mechner’s Prince of Persia footage, before it was traced and turned into game assets.

This sheet would then be digitised into the Apple II and cleaned up, pixel by pixel. The new process was faster. A VHS tape could be played back immediately to see what had been recorded; mistakes could be rewound and a new recording made.

Sure, there were easier ways to create graphics, but Mechner wanted to raise the bar. “I appreciated good animation – Disney animation,” he says. “I’d grown up on that since I was a kid, and the fluidity and illusion of life was wonderful to me.”

Mechner had tried to create animations without a filmed reference, but he felt the movement always looked artificial. “You could see that they had no weight and they never quite looked right,” he says. “My vision was to have a character who felt fluid and lifelike so that players would feel suspense, knowing if they moved too far, they could fall into spikes and that it would really hurt. Rotoscoping was my answer, and I found out Disney animators had used the technique as well.”

Read more: Prince of Persia The Lost Crown announced

Prince of Persia was a masterpiece of game design. It gave players just 60 minutes to lead the Prince out of a network of dungeons to save his imprisoned lover from the evil clutches of the power-hungry Jaffar. Cutscenes and explanatory text progressed the narrative, while the game itself was high on tension.

The Prince battled against enemy swordsmen, avoided spikes and deep pits, and used pressure pads to open time-sensitive gates. The fluidity of movement saw the Prince hang on to ledges, pull himself up, and leap across chasms with a human-like fidelity.

“I was taking the puzzle-solving, exploring aspects of a platform game and combining it with the visceral sense of danger of an Indiana Jones movie,” Mechner says. Much of his inspiration also came from the 1983 game, Lode Runner, which he felt would work well in combination with the cinematic drama of Karateka. “Yet with Lode Runner, you didn’t feel a sense of jeopardy; it was abstract, and you were only really trying to beat the level.”

Mind over matter

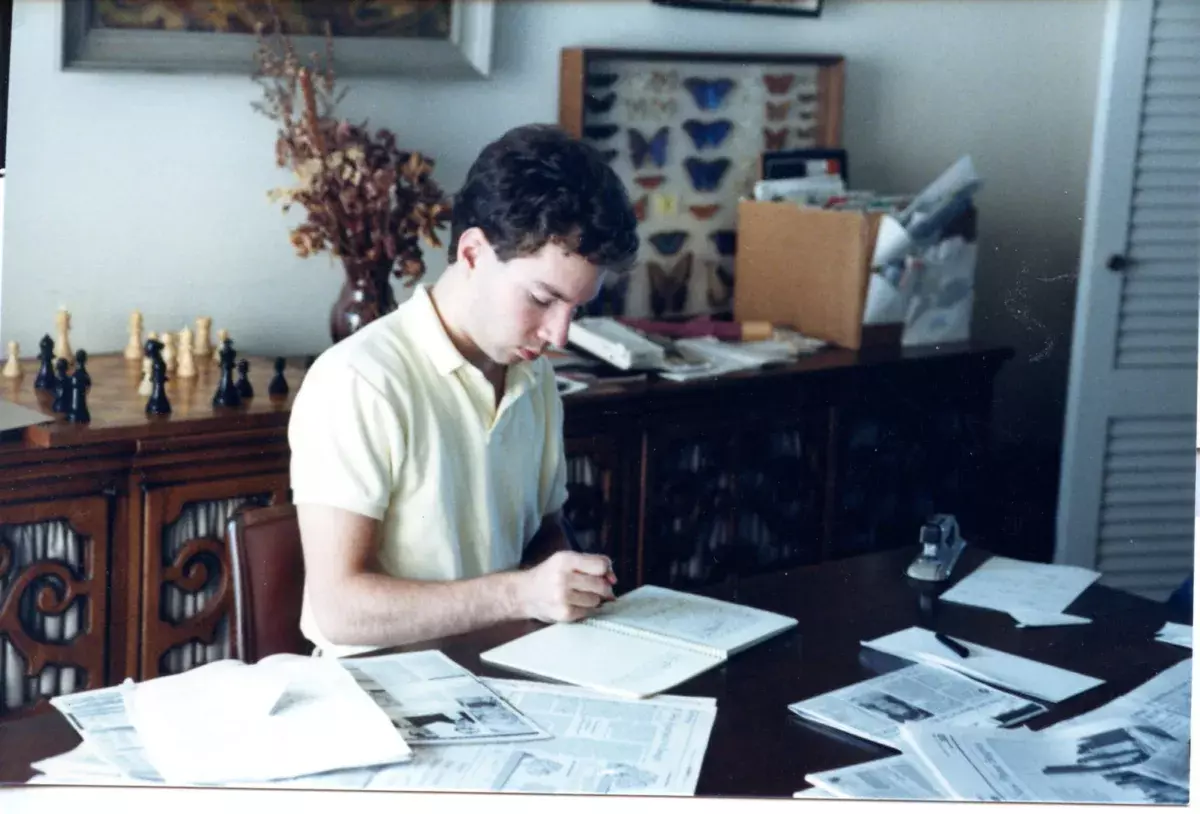

During the development of these games, Mechner kept a journal. As well as using it to sketch his ideas – “I’ve always started with notes and sketches on paper because it’s the most natural way to work,” he says – he laid down his thoughts, struggles, and worries. In 1985, for instance, he questioned: “Will there even be a computer games market two years from now?”

He also pondered whether he should be writing Hollywood scripts instead. “I’ve kept a journal since I was in college, and I find it very helpful to work through ideas,” he explains. “It also enables me to put my thoughts and emotions down on paper, and I think the act of journaling has great value. Sometimes when you look back years, even decades, later, you can find a surprise.”

One of these journals has formed the basis of a new book – the 30th-anniversary edition of The Making of Prince of Persia. Originally released as a self-published e-book, Stripe Press encouraged Mechner to update it.

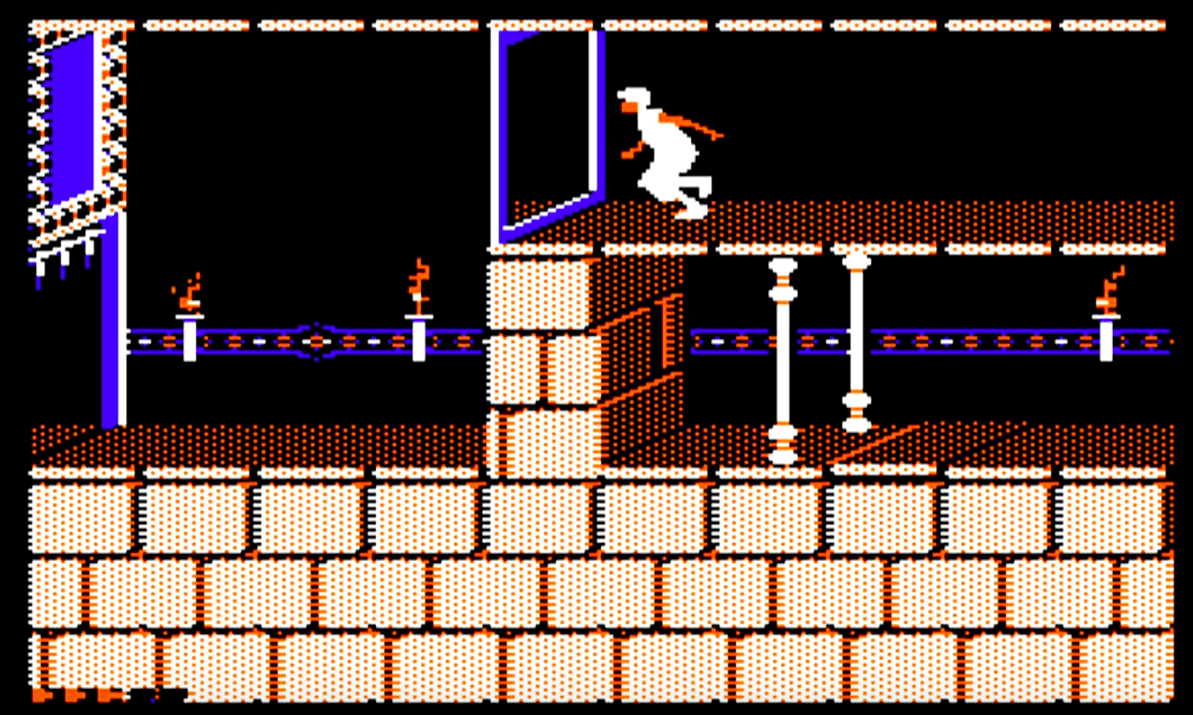

The famed mirror scene from Prince of Persia, haunting our dreams ever since.

As such, he’s added illustrations and annotations explaining his design concepts. “There are parts of the journal that might be especially interesting to game developers because, as designers, we struggle with the same issues,” Mechner says.

“It’s also interesting to see the ways in which the industry has evolved and the ways in which it has stayed the same. We still have crunch, battles for QA time, and struggles with marketing. There’s still an emotional rollercoaster of trying to do something that you’re not sure is going to work.”

“Journals can set your memory straight – you can’t deny what happened in the past because you’ve got a primary source that can teach great lessons and perspectives,” Mechner says.

Mechner has certainly experienced his share of highs and lows. He was delighted when Prince of Persia was widely acclaimed by critics, and saddened when sales were initially slow (the Apple II version sold just 7000 copies in its first eight months or so).

But as word got out and the game was ported to other machines, those sales increased hugely. “It’s always worth remembering that finished products don’t just spring into being,” he says. “As can be seen in my journal and in other people’s memoirs, production can be dicey. Creators can be a mess. They don’t have all of the answers, and yet that can give others hope.”

Levelling up

As if to underline that struggle, Mechner turns our attention to Prince of Persia’s level design. At first, he intended to include his level editor on the floppy disk, just as the developers of Lode Runner had done with their game. That didn’t happen, but the tool was so flexible that Mechner ended up using it to rapidly draft and rework Prince of Persia’s levels.

Nevertheless, Mechner’s pursuit of perfection took development to the wire. “Most of the final twelve levels that everybody knows were built or rebuilt in the last couple of months before the game shipped, and everything that I had done up to that point, kind of became the first draft,” he recalls. “But that ability to iterate quickly to build new levels was really valuable. It allowed me to fine-tune the difficulty and sense of adventure. We’ve lost that today with games that are so extensive.”

The pioneer today: it’s Mr Jordan Mechner.

Variety was important to Mechner, because he wanted to avoid repetition in his level design – a real danger, given that his dungeon was made from relatively few set-pieces. “I was looking at creative ways to use those pieces,” he says.

“I was asking myself how I could recombine falling floors and pressure plates in a way that was different from the way we’d already done it ten times before. So the level design was a combination of storytelling, pacing, and managing the difficulty of teaching the players skill. I wanted them to eventually master the challenges that were so tough at the beginning.”

Just as crucially, Mechner also wanted the levels to play out in a film-like manner by keeping things tense. “In arcade games, the general rule was to have three lives,” he begins. “But, in Karateka, I had a short enough story to just have one and, with Prince of Persia, where the levels were longer and greater in number, I had more thinking to do.

“I felt limiting lives would be too mean to the player, but that infinite lives would lose the tension. So I used a health indicator and placed potions around the levels that would top it up. Taken with the 60-minute time limit, I’d still allow the player to get sweaty palms as they tried hard not to die, but they’d also get a lot of gameplay under their belt before that point.”

Evolving over time

Prince of Persia 2: The Shadow and the Flame continued the theme set in the first game, albeit with more combat and the further headache of having to fend off up to four attackers. There was a 75-minute time limit this time around, while Mechner took on a different role in the game’s making.

“We had a programmer, sound designer, and artists for that game and I was the creative director,” he says. For this title, Mechner’s sketches and script were used to guide the development team, and it continued to ratchet up the tension and suspense that you would find in an action movie.

“I always liked that feeling in Prince of Persia where you think you can make a jump and, when you do, you get this huge feeling of satisfaction,” he says. “There’s a sense that, if you miss, it’s your fault, but that you can get it right next time and make it through. This created those little movie moments like pushing a guard off the ledge with your sword and seeing them fall on to spikes or backing them into a slicer. It’s like when Indiana Jones backed a Nazi mechanic into the plane propeller in Raiders of the Lost Ark.”

After the Prince of Persia sequel, Mechner largely moved away from the series, only briefly consulting on Prince on Persia 3D, published in 1999. He founded Smoking Car Productions and brought together a team to create a real-time, non-linear adventure called The Last Express, which took four years and a $5m budget to make. Again, it used rotoscoping, this time with professional actors filmed against a blue screen.

“It was a real labour of love recreating the 1914 Orient Express from our studio in San Francisco,” Mechner says. “It involved a pretty sophisticated, automated digital rotoscoping process, and it combined my filmmaking studies with everything I learned from making the Prince of Persia games.”

Mechner (pictured right) had a professional studio set up for the rotoscoping technique used in The Last Express, with actors set against a blue screen.

Thousands of frames of animation were created making use of CD-ROM and computers with many times more memory than the Apple II. “In order to rotoscope that many frames, we had to automate it, so we built and patented a process to turn film footage into something resembling a kind of pen and ink drawing,” says Mechner. “We were inspired by Art Nouveau, and we didn’t want it to look like full-motion video, but more hand-drawn.”

Banks of Macs were needed for the 3D rendered interior of the train, and the resulting game felt akin to an art film. A lack of marketing meant that The Last Express didn’t, sadly, get the attention it deserved – a fate that thankfully wasn’t shared by his next game.

In the early 2000s, Mechner was approached by Ubisoft, who planned to reboot Prince of Persia. “I took what I learned from The Last Express and made my first real-time 3D game,” he says, referring to the 2003 release of Prince of Persia: Sands of Time, on which he was credited as game designer, writer, and creative consultant. The game revitalised the series, spawned several sequels, and gave rise to a Hollywood movie.

Mechner played an important role in those later iterations of Prince of Persia, but he still retains a fondness for the earlier games. “Part of the charm was that the technology was so limited, which gave them a kind of handmade quality,” he muses. “But they still combined storytelling with exploration, which is what has always fascinated me about video games.

“Interactivity, and the player’s freedom to explore, are in opposition to the control a storyteller has to shape an experience to a certain end. But when those two opposing principles work in harmony, it can be wonderful.”

The Making of Prince of Persia is available now from jordanmechner.com. This article originally appeared in issue 37 of Wireframe magazine.