The developers of Lair of the Clockwork God, OneShot and The Procession to Calvary discuss the joys and perils of breaking down the fourth wall between game and player.

The term comes from the theatre: the idea is that in addition to the three walls on stage, there’s an imaginary fourth wall that the audience can see through, but the actors can’t. So when an actor breaks that fourth wall, it’s an exciting, unexpected event – an acknowledgement of the artifice of it all, a recognition that they’re in a play, in a theatre, talking to an audience. A sudden grounding of the suspension of disbelief.

Video games have been breaking the fourth wall almost from the day they were invented. Every time you’re told to ‘press A to jump’ and the like, the game is acknowledging the space outside the game world, breaking the illusion. But some games go further than that, leading to some of the most memorable moments in video game history.

“The one that always sticks out so beautifully for me was Arkham Asylum,” says Dan Marshall of Size Five Games fame. “You get sprayed with Scarecrow’s gas, and then it does a fake game crash and starts the intro again. And your heart stops, and it’s horrible, and then the intro plays and it’s slightly different, and it just eases you into the fact that this is part of the gag. That one always sticks out to me.”

Joe Richardson is a fan of how Lair of the Clockwork God regularly toys with the fourth wall. “I mean, that was fantastically meta, wasn’t it? I enjoyed that a lot.”

For Eliza Velasquez, who coded the fourth-wall-breaking OneShot, the indie horror game IMSCARED: A Pixelated Nightmare was a standout. “It’s a very cheesy horror game, but one of the things that it did was, after you finish playing the game, a minute later there would be a jump scare on your desktop – which is really, really mean, but I thought it was kind of cool,” she says. OneShot artist Nightmargin, on the other hand, has vivid memories of a game called Hello Penguin. “It does some very freaky things with your computer,” she says, “and I’m just going to leave it at that.”

Whether it’s Undertale’s acknowledgement of your terrible decisions or the cheeky narrative tricks of the Metal Gear games, we’ve all got our favourite fourth-wall-breaking moments. But what makes them so good?

3,000 WORDS?

“The stuff that influenced us quite a lot was all the old LucasArts games and all the old point-and-click adventure games: they always had this paper-thin line between the game world and the real world,” says Marshall, who created the genre-defying platformer/point-and-click Lair of the Clockwork God alongside Ben Ward. For him, the beauty of fourth wall breaks is that they acknowledge the presence of an actual human pulling the strings behind the scenes. “Like in Sam & Max Hit the Road, there was a line that always stuck out for me, where you pick up the big piece of twine and he says something like, ‘You always need a long piece of rope in games like this’,” says Marshall. “I love it when games do stuff like that – it makes you feel that the developers have remembered you, and there’s a direct connection.”

That Ben acknowledges he’s a character in a point-and-click adventure – and that Dan would rather be in a platformer – is key to Lair of the Clockwork God.

Marshall says that fourth wall breaks work particularly well for games by indie developers or enigmatic game designers like Tim Schafer, people who players feel like they might already know through social media or by following their work. “You’ve got that vague, weird connection with the developer, and I think that’s why the fourth wall stuff worked super-well for me, because you’ve got a sense of a link – like this was made for me,” he says. “It builds a connection between the player and the developer: you’re in on the same jokes as them.”

Jokes that break the fourth wall are often the most funny and memorable, simply because they’re so unexpected. But Joe Richardson, designer of the point-and-click adventure The Procession to Calvary, says that these gags tend to evolve naturally rather than being planned in advance. In Calvary, a game stitched together from Renaissance artwork, the fourth-wall-breaking interjections from God came about through circumstance. “I was looking to make a heaven scene,” says Richardson, “and so I was looking for paintings with clouds and people being debauched, or whatever, and didn’t find much. But I had this God, I had the cherubs, I liked them, and I wanted to get them in there somewhere. I tried to build a scene with God and the cherubs, and I couldn’t make it fill the whole screen, because I didn’t have enough art. So that’s where the idea of panning up to it [came from] – because I couldn’t fill the screen with artwork.”

Suggested product

Film Stories issue 53 gift bundle: Magazine + Nic Cage scratch poster + Nic Cage coasters!

£30.00

Suggested product

SPECIAL BUNDLE! Film Stories issue 54 PLUS signed Alien On Stage Blu-ray pre-order!

£29.99

God ended up acting as a stand-in for Richardson himself, offering asides and apologies about the making of the game. At one point, the cherubs begin ribbing God about the quality of the animation. “I quite often write bits like that, and then they’re not funny so they don’t go in,” he says. “But I just wanted at all costs to keep the reference to Macromedia Flash MX in there, as a nod to the good old days.”

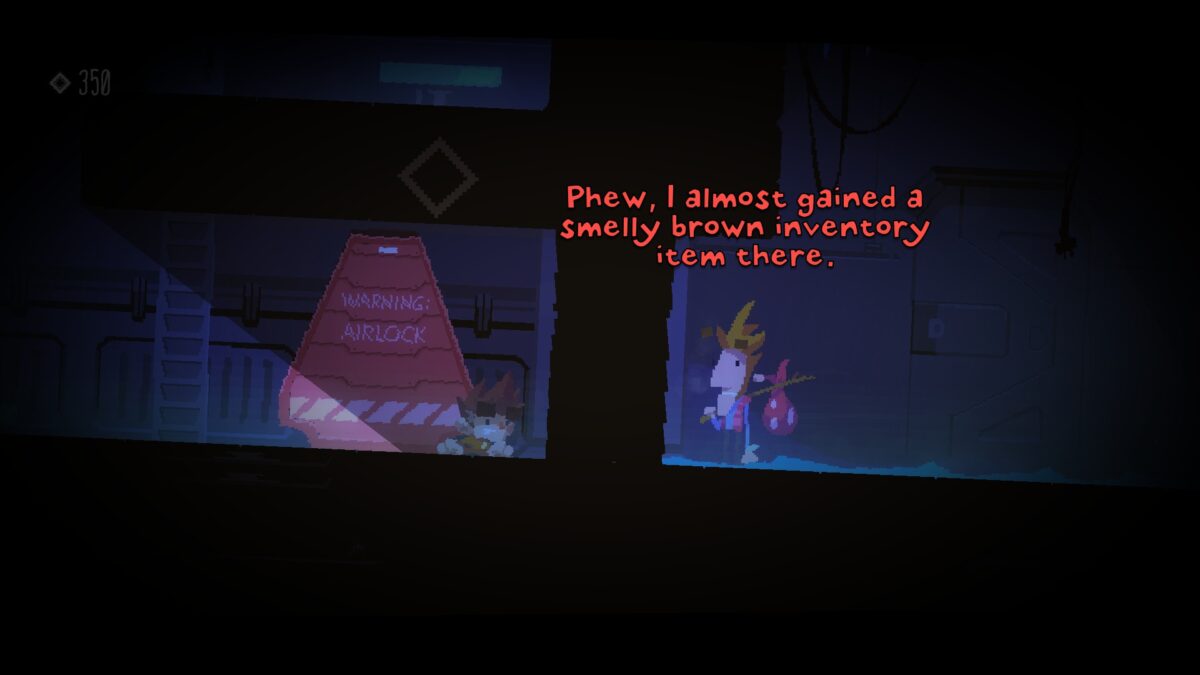

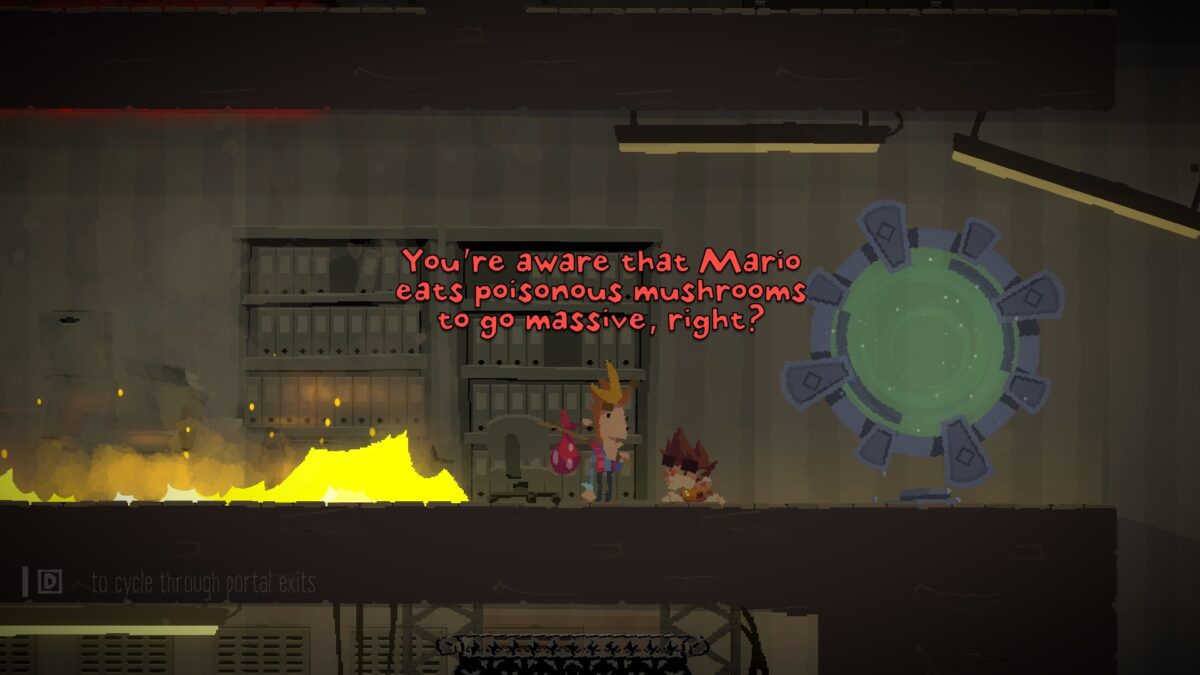

Referencing other video games is one of the many ways in which Lair of the Clockwork God acknowledges the world beyond the confines of the game.

800 WORDS INTO THIS

The fourth-wall-breaking jokes in Lair of the Clockwork God arrived through a similarly organic process. “What happens in development is that [me and Ben] go to the pub, and stuff that makes us laugh goes into the game,” says Marshall. “And the [redacted] was one of those things that made us laugh, and we were like, ‘That’s really funny and interesting and unique, and it’s a good selling point’ – because people would be like, ‘You’ve got to play this game, man, I can’t tell you why, but you’ve got to play it’.”

You may have noticed my sneaky censorship there, and that’s because the trouble with fourth wall breaks is that they lose their impact if you know they’re coming. There are a few dalliances with the fourth wall in Lair of the Clockwork God, but one in particular is phenomenally good, and Marshall is keen to preserve its mystique for players who’ve yet to experience it. “When Clockwork God came out, and there were a lot of people doing Let’s Plays on YouTube, I would skip to the bit where they found out about the [redacted] and just watch people break down in floods of tears laughing,” he says with a grin.

The surprise is key to successfully breaking the fourth wall: whether it generates fear, shock, or laughter. Or, indeed, all of the above, like when Marshall made a game for his girlfriend when he was a teenager. “Right in the middle, I made it cut to black, and I brought up the DOS font and put this thing up about how it was formatting the hard disk. I watched her play it, and she freaked out – and then burst out laughing when she realised,” he chuckles. “Watching her experience… that was one of those things that’s always left me a little bit keen to implement more of that sort of stuff.”

OneShot sometimes asks you to look outside the game world to find answers to certain puzzles.

NOT ENOUGH WORDS YET

Then again, less is usually more when it comes to breaking the fourth wall. “It’s something I think you have to be sparing with,” says Richardson. There’s a point where one of the characters in his game starts talking about the fonts for the dialogue. “Part of why it’s funny is because it’s so surprising that it happens,” he explains. “Even doing it twice, the second time… it doesn’t take you by surprise.” Indeed, there were a few more fourth wall breaks that Richardson considered for The Procession to Calvary, but held back to avoid taking away the impact of the others.

Marshall agrees that it’s important to avoid doing it too much. “We were quite careful with Clockwork God,” he says. “I think I’m worse for [resorting to fourth wall breaks] than Ben is when we write. I suspect he probably took some out when he did his big edits. It’s just like any joke: it’s funny once, and it’s kind of funny twice, and then by the third time it’s not funny at all.”

Richardson thinks there are some games where breaking the fourth wall wouldn’t be appropriate at all, like in the detective game Paradise Killer. “That’s one where I wouldn’t have liked fourth-wall-breaking, because I was quite immersed in its weirdness,” he says. “I think the reason it’s OK for point-and-click games to do it is because you’re not immersed in a point-and-click game: it’s so 2D, and the interface is right there. But Paradise Killer was one of the few games I did get immersed in, and so fourth-wall-breaking wouldn’t have been welcome.”

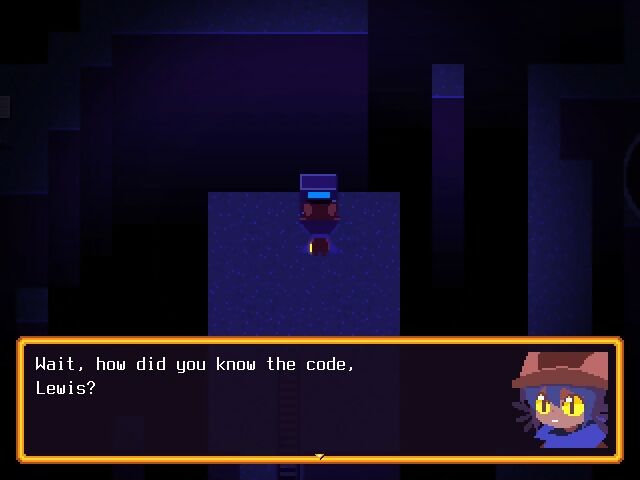

Early on in OneShot, the game acknowledges the existence of the player, which becomes key to the game’s plot.

There’s also the worry that fourth wall breaks can go wrong, or grow too obtuse. “One of my favourite games is The Sea Will Claim Everything,” Richardson reveals. “It’s a very word-heavy point-and-click game, and it has, I think, just one fourth wall break, [and it] stumped me. I got stuck and I needed to consult a guide. When I saw the answer was that it was a fourth wall break, I was very, very annoyed. Not because I didn’t like it, but because I didn’t get it.” Gags that break the fourth wall might require an element of surprise, but if puzzle solutions rely on looking outside the game world, the player needs to be primed to expect it. Marshall was careful to prepare players in Clockwork God: the start screen bombards players with a seemingly endless sequence of made-up company logos. “The last one’s called Setsa Tone Foundation, because it does,” he says. “It makes people, right from the start, [think that] unexpected things will happen.”

The great joy of fourth-wall breaks is that they allow for huge leaps of imagination and bursts of originality. “We specifically made things that toy with your expectations,” says Marshall. “And we specifically made things that make you question what a game is allowed to do. Putting a solution to a puzzle in an entirely different game I think is great.” He’s referring to Devil’s Kiss, a visual novel that accompanies Lair of the Clockwork God and that is key to completing a particular sequence.

But originally, he wanted to go even further than that. “There was going to be an optional puzzle, [where] there was a door that you needed a code to get through,” he says. “I was going to ask indie dev friends to put a graphic in their game somewhere.” The idea would be to play these other developers’ games to look for codes hidden in the visuals, then piece them all together to unlock the door. Marshall scrapped the idea in the end, but kept the door, which is unlocked by obtaining all the game’s achievements and solving a puzzle based on the images of each one.

The Procession to Calvary is packed with amusing comments on the game’s world, in addition to more overt fourth-wall breaks.

I’M WAY OVER DEADLINE

Richardson thinks that some people just don’t like fourth-wall-breaking in general. “However much it fits in, however immersed or non-immersed they are to start with, they’re just against it on principle for whatever reason,” he says. “I suppose it’s a debate that people like to have: where do you stand on fourth-wall-breaking? I think you have to go one way or the other. You can lean into it, like Clockwork God, or you can be a bit more subtle.”

In OneShot, the game’s whole premise is based on breaking the fourth wall. Early in development, Velasquez decided to make the player an integral part of the game world. “What if you and your character are two different people, and you’re going to talk?” she remembers thinking. “Then everything came out of that in terms of the way Nico behaves as a character. We wanted somebody [who was] very likeable. You want to like this person and protect them.”

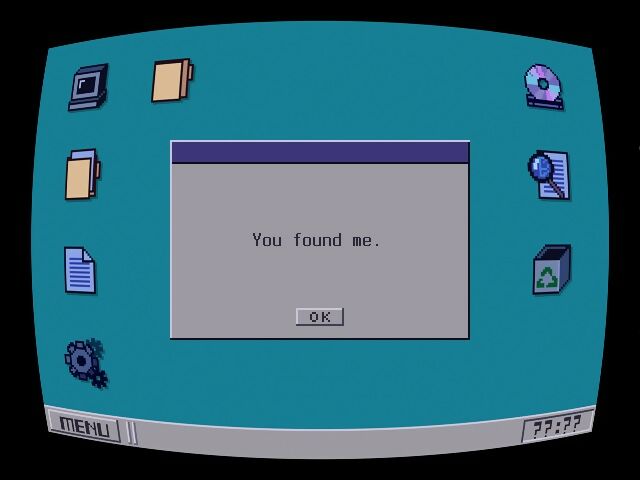

Near the start of OneShot, there’s a moment where Nico becomes aware of the player’s presence, who they interpret as a kind of god who controls events. It’s reinforced by messages sent from the game to your computer in the form of dialogue boxes – and later by other events outside the game, which I won’t spoil here. But the plot’s centred on the idea that the game world only exists on your computer, and only when the game’s running. Indeed, in the initial 2014 build, closing the game without saving had dire consequences. “In the original one, if you quit without going to bed, Nico dies,” recalls Velasquez. “I regret that a bit, because it was super-edgy.”

The original 2014 version of OneShot would permanently kill the main character if you turned off the game without saving, but this was removed in the later Steam release.

Far from depleting immersion, OneShot’s fourth wall breaks heighten it, inviting the player to care deeply about the game world. “Something that I really wanted to push hard on for OneShot is that the breaking of the fourth wall isn’t anything unique or special,” says Nightmargin. “The casual approach to it makes a game like this feel special by, ironically, not treating it as something special.” The developers also wanted to avoid the use of fourth-wall breaks to frighten the player, as in horror games like IMSCARED. “We wanted to get across that the fourth-wall-breaking isn’t here to hurt you, it’s here to be your friend – even though it can freak you out at times. It instils in the player a sense of responsibility, which is perfect because we want the player to feel responsible for Nico, but also [for] the world itself.”

One problem, however, is that the fourth-wall breaks in OneShot are intimately tied to the functions of a PC – which has caused headaches for developer Michael Shirt while he’s been preparing the game for release on consoles later this year.

“The idea we ended up going with was creating a fake desktop,” he says. “So everything that would happen on the PC in the normal game happens in that environment.” Doing anything quirky with the console beyond the game itself was unfortunately off limits: “The first parties aren’t really happy about you messing with files and stuff,” he laments.

THANK GOD, NEARLY THERE

Ultimately, video games are the perfect medium for breaking the fourth wall because of their interactive nature, and the intimate tie between the player and what’s happening on screen. The very concept behind OneShot wouldn’t work anywhere else. “It’s something you can only do in a video game, which I think is extremely unique,” says Velasquez. “A play or a movie can break the fourth wall, but you’re very limited in what you can actually do with that.”

User interface elements like hotspots are sometimes referenced directly in The Procession to Calvary.

Richardson, for his part, plans to ramp up the fourth-wall breaks in his next game, Death of the Reprobate. In fact, God (aka Richardson) is set to appear in almost every scene. “I’ve got this world where you’re going around looking for good deeds to do,” he says. “So I wanted to have some sort of indicator on the people who are the quest givers.” He didn’t want to add a clunky UI element, and initially thought about marking the characters with a cloud, with a sad face on it. “But this cloud looked [rubbish], so I decided to put God in there,” he says. “These characters now have a big red arrow painted on a bit of wood that hangs above their head. God’s hiding in the background with a fishing rod, holding up the sign.”

At the game’s start, the player asks a quest giver how to find people in need. “And he says, ‘The Lord will guide you’,” laughs Richardson. “And then you walk into the next scene, and God’s there holding up a UI sign. And then potentially, at the end of the game, it could turn out that it wasn’t God, it was just some guy. ‘You’ve been following Derek? Derek dressed as God? I meant spiritually God will guide you, you fool!’”

A version of this article was originally published in issue 66 of Wireframe magazine.