At the end of Batman Begins, as Christopher Nolan drops the ‘joker’ card as a whopping great clue to what might come next, Jim Gordon (Gary Oldman) asks our hero “what about escalation?”. It’s a good question in relation to what becomes Nolan’s one and only trilogy. If anything stands as escalation, it is The Dark Knight.

Many of us at the time recognised Batman Begins as something special; an earthy yet epic, philosophical combination of traditional blockbuster and post-postmodern superhero film. Nolan originally never intended on a follow up (or so he said), having explored the genesis of the Bat as a symbol, but he clearly couldn’t resist the opportunity to return and explore what it means when such a symbol can be corrupted. It immediately sets The Dark Knight apart as a sequel, not simply an excuse to revel in a new, fully formed Batman. Nolan’s primary impetus in returning to the world of Batman is to deconstruct the very idea of him.

He talked about the idea of the Joker card in the previous film:

We wanted to suggest possibilities for how the story would continue, not because we knew we were going to make a sequel, but because that was the feeling we wanted the audience to leave the theatre with. The ending of Batman Begins was specifically aimed at spinning off that element of the mythology in the audience’s mind so that they could imagine what The Joker would be in that world.

Nobody, I think, was quite prepared for just how impressive The Dark Knight turned out to be.

For my money, it remains to date Nolan’s finest picture. It could well be the greatest comic-book movie ever made. It would be hard to not include this film on such an auspicious list. It doesn’t simply repeat the tricks employed in Batman Begins, it builds on everything Nolan delivered in that film, from narrative structure to character work. The Dark Knight feels rich and visually powerful in a manner Nolan only could have pulled off after The Prestige, which as I previously discussed, honed many of the techniques he employed across his career subsequently.

So many factors contribute to why The Dark Knight is so impressive. The reality of the production design and setting for one. Batman Begins crafted a more familiar, art deco Gotham in Shepperton Studios and while technically and visually impressive, you could tell this was an artificial Gotham. Not so here. This is Michael Mann’s Gotham. This is a Chicago-style metropolis where you can hear the sirens, smell the air, feel the ground beneath your feet. Nolan changes his colour palette to best reflect a stage of corruption and power happening within a modern American city. This is undoubtedly the most realistic Gotham portrayed on screen. That makes the hyper-reality of the film’s primary draw all that more terrifying.

I’m talking, of course, about Heath Ledger’s Joker. An unnamed force of nature, filled with various different backstories depending on who he talks to and when, as he describes an “agent of chaos” who immediately banishes Jack Nicholson’s playfully devilish Jack Napier from the 1989 Batman out of our minds (as great as that performance remains) and cements the Crown Prince of Crime for the 21st century.

It is such an incredible performance. Whether it contributed to Ledger’s tragic and untimely death soon after filming is open to debate, but either way it stood as a haunting elegy that draped over The Dark Knight but only added to the magnetism and legend of his immersive portrayal. Ledger is gone here. This is as Method as it gets. The Joker is a fascinating, destructive, mercurial and chilling presence. And incredibly, he is only on screen for around 30 minutes in a film that touches 150.

Previously: Revisiting Christopher Nolan’s Memento Previously: Revisiting Chistopher Nolan’s Insomnia Previously: Revisiting Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins Previously: Revisiting Christopher Nolan’s The PrestigeWhile the Joker has always been Batman’s chief antagonist, often portrayed as a camp, cackling menace (many of us grew up as much with Cesar Romero’s pantomime version from the 1960s Batman TV series), he is psychologically placed in The Dark Knight as a check against the ideology of Batman and Gotham City. Nolan ends up framing his trilogy in regards to Batman in three stages – Batman Begins is about Bruce becoming Batman, The Dark Knight is about Bruce losing Batman, and The Dark Knight Rises is about Bruce rediscovering Batman. Broadly, that serves as his arc. Within that, the villains directly challenge not just his psychology but his ideology.

We saw Ra’s al-Ghul create a monster, in a sense; he trained Bruce presumably as a possible successor, hoping he would help him destroy the fallen Gotham. We see in The Dark Knight Rises how Bane encourages revolution under the guise of vengeful totalitarianism to finish what Ra’s started. The Dark Knight bridges the gap via the Joker as he works to prove Ra’s thesis, that Gotham and it’s people are beyond saving. Bruce refused to believe this in Batman Begins, killing his mentor to save the city that swallowed his family in a belief people could be better. The Joker is not a man concerned with power, or status, or even living necessarily. As Alfred (Michael Caine) puts it, “some men just want to watch the world burn”. The Joker quite literally burning the financial resources of the city’s underworld underlines this.

The Dark Knight is far more a film about the destruction of Batman as a symbol rather than Gotham as a city, but Ledger’s Joker is without doubt the latter-stage formation of Joaquin Phoenix’s nascent portrayal in Todd Phillips’ Joker a decade later, the next significant characterisation (let’s ignore Jared Leto, shall we?). Joker may present a clear, established backstory for Arthur Fleck, but this could easily have ended up morphed, twisted and outright embellished by the time he becomes Ledger’s Joker.

The Dark Knight’s villain is less of a theatrical menace and more of a sociological terrorist, cutting through the narrative in order to stoke Gotham’s broiling fire, test the limits of Harvey Dent’s police force, provide ethical dilemmas to challenge Batman — to create anarchy from order. “You see, their morals, their code, it’s a bad joke. Dropped at the first sign of trouble. They’re only as good as the world allows them to be. I’ll show you. When the chips are down, these… these civilized people, they’ll eat each other. See, I’m not a monster. I’m just ahead of the curve.”

Suggested product

SPECIAL BUNDLE! Film Stories issue 54 PLUS signed Alien On Stage Blu-ray pre-order!

£29.99

What Nolan is exploring with this trilogy feels ahead of the curve too. The Dark Knight was released in 2008, the same year Barack Obama would be elected as President to usher in what was considered a progressive, Democrat-led age for American and maybe even world politics. Iraq had been dealt with. Bin Laden was on the run. Daesh had not yet risen. For a while, we could have been turning a corner away from the monstrous darkness lurking beneath society, or so it appeared. Even the financial crash of 2008 and subsequent global recession did not necessarily have an immediate effect on Western democracy. Obama won a second term in the same year as The Dark Knight Rises was released. Maybe the Joker’s final words in that film didn’t have to be prophetic. “You see, madness, as you know, is like gravity. All it takes is a little push!”.

In that sense, the Joker here stands at the end of one system and the beginning of another, as we have seen in the last 15 years. He takes a dignified, honourable centrist in Dent, and transforms him into a divided, polarised split personality of rage and hopelessness, literalised as Two-Face. Some might argue Aaron Eckhart (who is superb throughout) gets too little to do in this villainous guise, but Two-Face is expressly designed to be a malformed reflection of Gotham’s decency. The whole purpose is for Harvey to have fallen (that Nolan trope again becoming apparent) and Batman having to lie, as Alfred does to Bruce about Rachel Dawes’ choice of future partner, for the greater good. “You either die a hero or live long enough to see yourself become the villain”, as both Dent & Batman say, in perhaps the film’s most iconic line.

This to me suggests that Nolan doesn’t believe in conventional heroism. He is sceptical about the idea of the ‘superhero’, especially. Can you ever class his Batman as such? I’m not convinced. As the critic Richard Newby writes:

Even more so than its predecessor Batman Begins (2005), The Dark Knight detaches itself from many of the tropes associated with superhero movies and instead operates along the lines of a crime thriller-drama devoid of world-ending stakes or shared universe connections. Nolan’s Batman operates as a public servant rather than a superhero.

That sounds less than grandiose but that’s the point. There are no world-ending stakes here. The Joker isn’t about to even literally destroy Gotham. This is a psychological battle framed as a crime epic. How else to explain Nolan’s choice of climax? Having Batman first forced to choose between the saviour of Gotham and the woman he loves, and then a moral dilemma as a ferry of prisoners opposite a ferry of free citizens must grapple with the decision to blow each other up or not. Granted, that climactic beat isn’t Nolan’s strongest, landing without quite the impact it should, but it underscores the point of the entire film. The Joker attempting to prove that society are just as in the gutter as he is. That chaos lurks beneath the veneer of civilisation.

Bruce on a personal level here struggles with the idea that Rachel (played with far wittier nuance by Maggie Gyllenhaal here) might want the ‘White Knight’ that is Dent. Batman troubles Lucius Fox (Morgan Freeman) by revealing a surveillance system on all of Gotham (albeit one he gives Fox the power to kill at the end). He is morally complicated at points, in contrast to Dent’s seeming all American virtue. Maybe that’s his point. Dent is easier to corrupt because he is a clear cut symbol. Nolan is drawn to characters – men especially – who are clawing their way back from under. Men who are flawed, who have failed, or live on the precipice of ruin. Often brilliant men, but men who are tainted by their own inner demons. Bruce Wayne here perfectly encapsulates that. Nolan perhaps believes more in the hero who can recognise his own flaws.

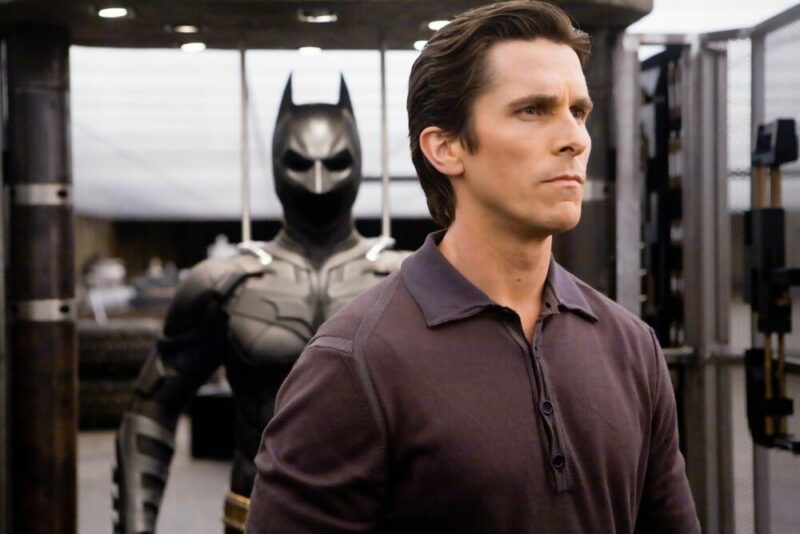

Credit to Christian Bale too, who oft-gets overlooked in The Dark Knight, under the weight of the titanic villainous performances and the sheer craft of the filmmaking. He must juggle emerging fully as a powerful, fear-evoking Batman and playing dual facets of Bruce – the haunted grown up orphan and the carefree playboy, all of which he does with aplomb. The key I think to Bale is that he makes you care about both Bruce and Batman, and you believe him when he fuses the two identities in combating the Joker with his own psychology. “This city just showed you that it’s full of people ready to believe in good” are lines that on paper could read rather ripe, but Bale makes them land. He is quietly the rock under which a great deal more sits, acting-wise.

There is simply a majesty about The Dark Knight. A feeling you are watching more than a conventional comic-book film or superhero movie. In truth, we’re seeing what examples of those genres can truly do, and while nobody quite has equalled the trick since (ironically not even Nolan himself, much as I love the last film in the trilogy), a great deal of what came next has been influenced by The Dark Knight, as indeed Batman Begins. It’s a dynamic work that cements what Christopher Nolan can do with storytelling, with set pieces (that truck flipping sequence alone) with the evocation of atmosphere. And it almost draws a line in the sand for the comic-book film. There is before The Dark Knight and after The Dark Knight. That’s the enormity of this film’s legacy.

It also presented Nolan with a challenge: how do you go bigger than The Dark Knight? His answer: to not just go deeper within, but in doing so create a world almost without limits.

— Thank you for visiting! If you’d like to support our attempts to make a non-clickbaity movie website: Follow Film Stories on Twitter here, and on Facebook here. Buy our Film Stories and Film Junior print magazines here. Become a Patron here.