Enhance Games executive producer Mark MacDonald tells us about the unused ideas, challenges, and six-year process of making the instant classic, Humanity.

Some of my favorite video game experiences, I came to realise recently, happened almost by accident. Katamati Damacy creator Keita Takahashi, for example, didn’t start out as a game developer – he was a fine artist. It took an unsuccessful pitch (for what would eventually become Katamari Damacy) and a six-month educational course before Takahashi finally switched careers and got the chance to show his ridiculous idea off to the world.

Similarly, Humanity director Yugo Nakamura was a web designer and artist long before he turned to game development. The story of Humanity’s making is a particularly fascinating one; in an alternate universe somewhere, Tetsuya Mizuguchi, the designer of critically-lauded Rez and Tetris Effect, didn’t pick up Nakamura’s tech demo – or spend six years helping to bring it to fruition. Fortunately, we live in a universe where all this did happen.

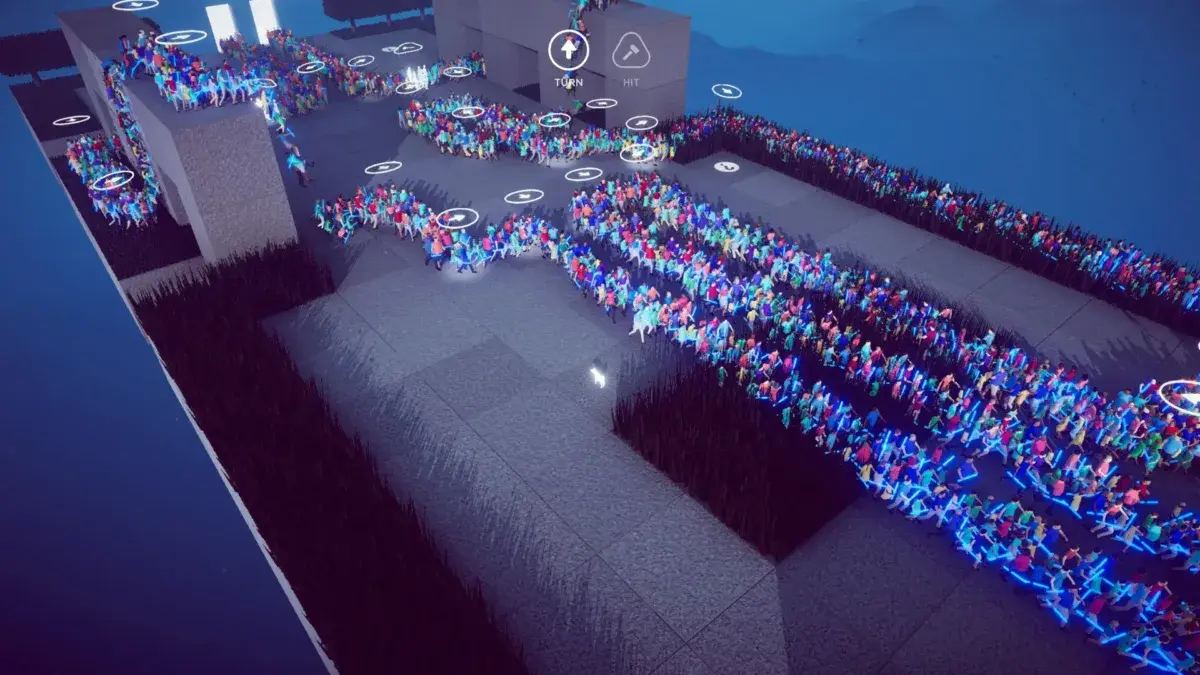

Humanity, for those unfamiliar, is the brainchild of Nakamura – founder of interactive Tokyo-based design studio Tha ltd – in which players guide an endlessly spawning flock of people using a Moses-like Shiba Inu. Your glowing dog can place commands on the ground, forcing the faceless mass to change direction, jump, leap, float, split and more besides. You then have to hope that, as in DMA Design’s classic Lemmings, your directions will lead your humans to safety.

Credit: Enhance/tha LTD.

It sounds simple on paper. But Humanity grows in scale and complexity as you progress, with later stages seeing thousands of figures leaping through the air or even fighting each other.

“As you might expect from the studio that turned Tetris into a visual and musical journey through life, the universe and everything,” Jon Bailes wrote in his review, “Humanity isn’t merely a puzzle game, it’s an existential trip.”

Before Humanity became the experience it is today – before it was even a game – there was much work to be done. So much work, in fact, that shaping Nakamura’s crystalline vision required additional manpower from Takahashi’s Enhance Games, which helped to balance Humanity, make it fun to play, and keep its director from becoming overwhelmed at the size of the task (“To be quite honest … I didn’t even want to show up to work,” Nakamura revealed to The Guardian recently).

Like many artistic collaborations, there was occasionally “something of a tug-of-war” between the director and his more experienced collaborators. “It was absolutely difficult,” says Mark MacDonald, an executive producer at Enhance, over a video call from Tokyo. “You want it to be a puzzle [game]. But we also wanted to lean into its action-y side and enjoy the fun parts of platforming. We didn’t want it to be like Sudoku.”

Credit: Enhance/tha LTD.

Of course, Sudoku doesn’t have great waterfalls of people falling to their deaths. Or people shooting deadly laser beams at each other. And while it might be amusing to watch thousands of ragdoll bodies march into an abyss at first, Mizuguchi and his collaborators saw it as a potential problem.

“We didn’t want you to feel pressure – like, ‘Oh my God, I lost a person! I need to restart the whole game’,” MacDonald explains, noting that it was particularly important for the team to find the sweet spot between turning players into cold-blooded leaders and making them feel empathy toward their tiny humans.

“We didn’t want it to be just lemmings, you know?” he says. “It could have been masses and masses of that. But it was very different when it was people – it felt different. You want people to care to some degree. But you don’t want them to feel like they’re terrible people.”

To this end, the team decided to add a note early on in the game, letting players know that no humans were harmed in the making of Humanity.

One early challenge was figuring out exactly how the game’s flock of people should be controlled – at some point, in a masterful stroke of design from Nakamura, a plain cursor was replaced by a shiny Shiba Inu. Perhaps one of the biggest headaches the team faced, though, was working out an efficient way of motivating players.

Credit: Enhance/tha LTD.

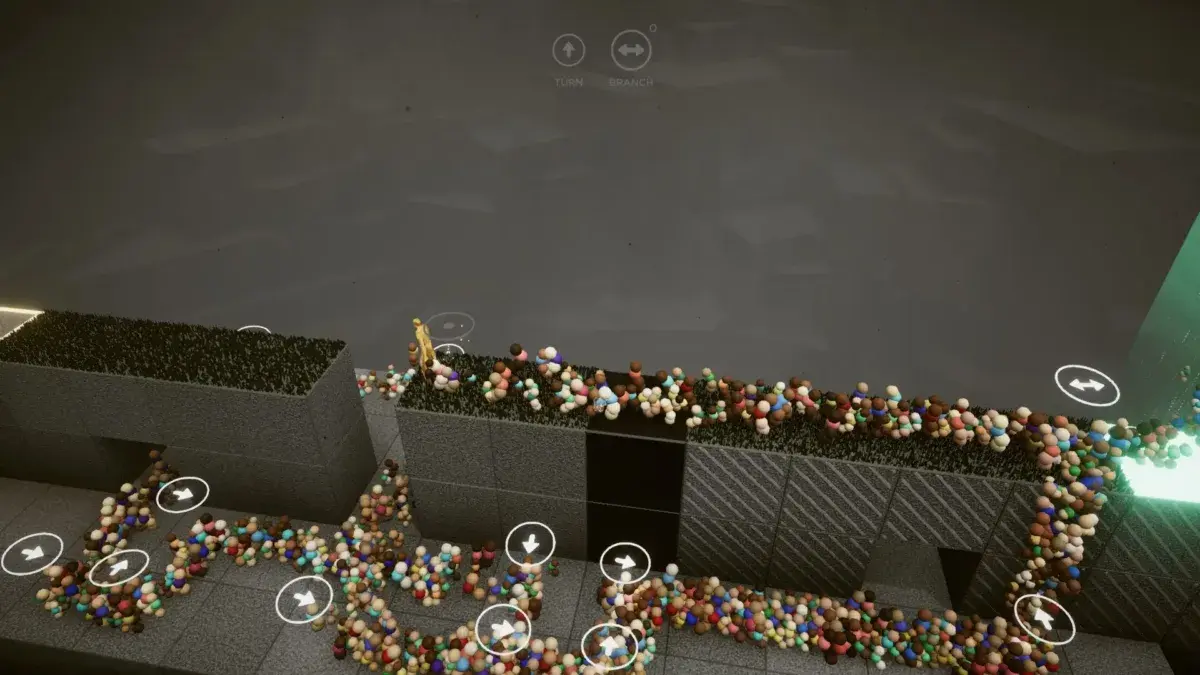

Since Humanity is already demanding, often requiring players to restart a level over and over in order to see where they went wrong, Nakamura and the developers at Enhance wanted to reward players without making them feel frustrated in the process. Eventually, they landed on a simple, yet elegant solution – optional, collectible items called Goldys.

“With Goldys, once we had it, it just felt right,” says MacDonald. “It solved a bunch of different things and is easy to understand. At the same time, [it’s] doing a lot of stuff that players may or may not even notice. It covers a really difficult part of making a game like this, which is accounting for people’s different play styles.”

As with Super Mario’s stars or Celeste’s strawberries, these golden statue-like collectibles are found in every stage. Should you not choose to go out of your way to retrieve them, the levels can be fairly easy. If you’re a completionist, collecting all Goldys will prove to be quite a bittersweet challenge, since they don’t respawn like your regular humans. Eventually, in order to move on and unlock the ‘boss level’ of each chapter, players need to gather a certain number of Goldys.

Says MacDonald, “It was this difficulty ‘safety valve’ where it was up to the player, hopefully in a non-annoying way, to decide just how much they wanted to challenge themselves. Also, if and when players came to a spot where the game’s like, ‘you need more Goldys to progress,’ they would be like, ‘Well, I liked this kind of level, so I’m gonna do this’.”

Credit: Enhance/tha LTD.

While Humanity isn’t a game you’d normally expect from Enhance, the studio behind Tetris Effect and Rez Infinite, it certainly shares certain values with the company’s past work. Particularly, how it manages to strike a harmony between gameplay, visuals and sounds without being too overwhelming – a Herculean task that took Mizuguchi and the team six years of tweaking and testing before it culminated in an emotionally moving experience that is Tetris Effect. Considering that, arguably, Nakamura’s baby has many more ideas and moving parts than “Zen Tetris,” it’s hardly a surprise to hear how much playtesting went into Humanity.

“Once you keep iterating, you [become less] able to trust your own judgment as much,” MacDonald admits. “We had mechanics or ideas for mechanics that seemed like they would be amazing but they just didn’t work out. Or maybe there was something there, but it wasn’t as cool as something else that we had, or simply didn’t feel like it fit correctly. It’s much more difficult than that with a game like Humanity. You really have to keep the whole thing in mind at the same time.”

According to Nakamura, who spoke with Edge magazine for the game’s preview, only around 20 percent of the team’s ideas made the final cut. We had to ask, then: what ideas were abandoned during the game’s development?

One of them was a command called ‘Charisma.’ “Basically it allowed you to influence a leader person, who then was able to go in and influence other people,” MacDonald tells us. It was a “conceptually interesting idea,” he adds, but one ultimately dropped due to the number of other concepts already present in the game.

“We ended up with levels where it was integrated and it was really fun. But we also realised it was a matter of choosing. We’ve already got so many ideas in here. We could have either spent more time polishing them up and bringing in another idea and rebalancing [everything], or take that time to iterate on the ideas we already have.”

Instead, the team opted to concentrate on balancing a handful of intricate ideas that complement each other in later levels. In the case of the ‘Follow’ command, which makes people obediently follow Shibu inu like a herd of sheep, proved to be a valuable addition in the final game. Although, not without one major tweak. At one point in development, the Follow command provided “a time machine function” because “it had people mimic whatever the dog was doing. So if the dog jumped, then the people would jump when they got to that exact part [on the stage].”

MacDonald likens the scrapped version of the command to Capybara Games’ 2D side-scrolling shooter Super Time Force in which the ghosts of your past lives replay your every move. But just as Super Time Force’s mechanic “nearly broke its creators’ brains” as they tried to shape it into something players could easily understand, the original version of the ‘Follow’ command also proved too difficult to keep track of, and was therefore simplified.

Humanity’s scale becomes even more impressive when you learn that all the puzzles you play through – perhaps with the exception of boss stages – can be recreated in the level editor. The construction element was a first for Enhance. Says MacDonald, “If I look at LittleBigPlanet or Mario Maker, it’s like, ‘Yeah, that seems hard to do.’ But that’s not even coming close [to Humanity].” He describes the process as akin to “creating a social network.”

Credit: Enhance/tha LTD.

Would Enhance have included a level creator if they understood the complexity of the challenge they were undertaking? “Honestly, I don’t know, because it’s such a huge, heavy lift,” MacDonald admits.

Of course, all the hard work team at Enhance put into it paid off eventually. Barely a couple of weeks into Humanity’s release, players had already made over 2,000 levels. “We were over the moon,” says MacDonald. “And the quality of them has been really outstanding.”

Since this was Enhance’s first brush with user-generated content, they turned for advice to a studio which has decades of experience in the field – Media Molecule, the award-winning studio behind LittleBigPlanet and Dreams. “They’re the gold standard,” MacDonald enthuses. “I mean, they did all these awards and were simply so good at how they handled it. They were kind enough to give us some key advice early on when we were just building the tools. And they were so gracious about it, too.”

Perhaps the most impressive thing that Humanity manages to accomplish, besides making all its moving parts work in tandem, is evoke the feel of the bygone era of games like PaRappa the Rapper, Katamari Damacy, Chu Chu Rocket and other creative experiences we see less often nowadays. Quirky games that “could have only been made in Japan,” as MacDonald points out. Here’s us hoping, then, that Humanity’s masterclass of creativity and design will inspire other developers to follow in its path.

Read more: Humanity review | People are lemmings