The Disbelieve spell turned Julian Gollop’s wizard v wizard battle royale, Chaos, into one of the most tense games on the ZX Spectrum.

With its 3.5MHz 8-bit processor and (relative) paucity of controller ports, the ZX Spectrum wasn’t a natural home for multiplayer games – much less experiences that allowed up to eight warlocks to battle one another on one screen. Ambitiously, though, this is exactly what 1985’s Chaos attempted with its turn-based, fantasy-themed battle royale. Granted, actually playing the seminal game in your typical 1980s bedroom would have been, well, chaotic – imagine eight players crowded around one keyboard, each waiting to take their turn, with rival players asked to avert their gaze while the current player selected their spells.

Chaos was, in essence, a digital board game, loosely based on an early tabletop title by Games Workshop. Programmed by a young Julian Gollop, later of XCOM fame, Chaos sees players take on the role of duelling necromancers in a turn-based fight to the death. At the start of each bout, players are given a random selection of spells, ranging from creatures, which can be conjured up on the battlefield and sent out to attack enemies, to one-off attacks like lightning bolts and fireballs. Then there are more defensive manoeuvres – you can magic up citadels to hide in, or wings which allow your wizard to move further across the board each turn.

The creature spells are by far the most common, and form the game’s tactical backbone; with the wizards themselves being weak in combat and only able to move one square at a time by default, conjuring an army of more mobile and physically formidable creatures is key to winning a bout of Chaos. Lower-ranking, less dangerous creatures such as rats and snakes are easy to cast since they have a high success rate; the more deadly the creature, the more likely the spell-casting is to fail, with dragons and vampires being among the strongest and hardest-to-kill beasts in the entire game.

But rather than risk wasting a turn on conjuring up, say, a Golden Dragon, only to watch the spell fail, players could instead opt for a handy alternative: when a creature spell is selected, there’s the option to cast it as ‘real’ or ‘illusion’. Choose illusion, and there’s suddenly a 100 percent chance that your Golden Dragon will successfully appear on the battlefield. There is, however, a tactical downside to creating illusory creatures: Chaos gives players infinite opportunities to cast a spell called Disbelieve. If a player suspects that a rival’s manticore is an illusion, they can just zap it with the Disbelieve spell and, if their suspicion is correct, then the creature will disappear in a dramatic flash.

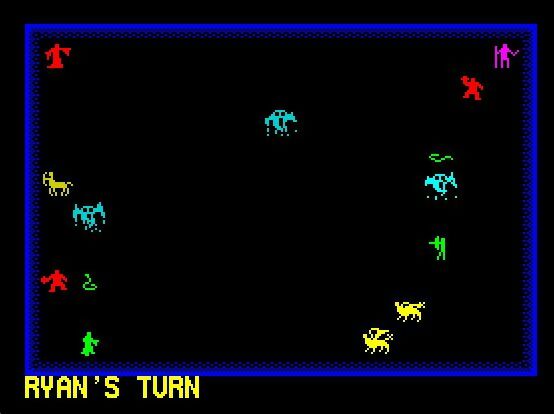

I’m battling against three computer-controlled wizards here. I’ve also taken the risk of casting an entirely illusory army of ghosts. Nobody’s cast Disbelieve yet, thankfully.

This single mechanic gives what could be a simple tactics game the sweaty tension of a high-stakes poker tournament; on one side, you can have a player moving their Green Dragon around the battlefield, heartlessly slaughtering an enemy wizard’s unicorns and dire wolves, but secretly terrified that a single Disbelieve spell could leave their illusory beast vanishing in a puff of smoke. In other scenarios, you could be in the midst of a tense battle, with your army of creatures severely depleted, your spellbook running low, and your last hope of winning the game being that the enemy vampire bearing down on you is an illusion. Holding your breath, you cast the Disbelieve spell… only to watch as it rolls off the creature’s cape with no effect. The vampire is real, and for you, the game is over.

Julian Gollop revisited his fantasy creation twice; once in 1990 with Lords of Chaos – more of a tactical RPG – and again in 2015 with Chaos Reborn, which returned the series to its claustrophobic, competitive roots. The latter also added the kind of detailed 3D graphics and online multiplayer functions that eighties kids could only have dreamed about – and the Disbelieve spell was, naturally, entirely present and correct. That such a mechanic was still so effective 30 years later is surely a testament to its timeless brilliance.

The enemy wizard, Bog, has cottoned on to my tactic, and has started casting Disbelieve spells on all my creatures. Damn.

Of course, as mentioned in that 1980s bedroom scenario outlined at the start of this piece, casting spells also required everyone crowded around the ZX Spectrum to avert their eyes while the current player selected their spell. When the game offered up its fateful choice – “Illusion? (Press Y or N)” – it was joined by a frisson of anxiety. That single decision could decide the fate of the entire game. And what if one of the other players in the room were to cheat, and sneak a look at which button they pressed? Well, that would surely be breaking some kind of wizardly code of conduct. Nobody playing Chaos in the 1980s ever did that.

Creating Chaos

Long before Julian Gollop programmed Chaos, he began establishing its rules by creating a card game. As he explained to Wireframe back in 2018, his duelling wizards scenario was not only inspired by Games Workshop’s 1980 tabletop game, Warlock, but was also a response to what he saw as its shortcomings. “The main thing I didn’t like about [Warlock] was that it was too abstract,” Gollop told us. “There wasn’t a sense that you were really battling against enemies, it was much more of a numbers-and-cards type game.” Gollop also came up with a concept that simply wouldn’t be possible in a traditional board-game: the Disbelieve spell. In a tabletop game, he explained, you wouldn’t be able to “tell the other players you’re casting Disbelieve, or roll a dice to see if you’ve succeeded or failed.” Instead, he said, Disbelieve “was something I deliberately added to [Chaos] because I knew it was something I could do on the computer that I wasn’t able to do with the board-game.” And thus, a tactical classic was born.