With huge spoilers, here’s a detailed look and a few thoughts on Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, that’s now out in the world.

Spoilers lie ahead for Oppenheimer…

Ripples in water. The very opening image of Oppenheimer reminded me of how Christopher Nolan began The Prestige, as we bore witness to a graveyard of top hats. That visage has always stayed with me. I suspect the evocative, dare I say explosive, ripples will do the same.

Much like the film itself, in fact. Every time I emerge from a Nolan movie, I wonder if it stands as the best film he has ever made. Even after Tenet, a picture forever trapped in that weird liminal space at the swirling fusion core of the Covid pandemic, as Nolan hedged his bets and pushed for the release of his film in cinemas. I vividly remember leaving Inception and Dunkirk believing he’d never top either of those.

The honest truth is, he already had. The Dark Knight remains unseated as Nolan’s crowning achievement to date for me, fifteen years on. There is magic to that movie. That’s a once in a generation picture. Oppenheimer, however, I am truly tempted to suggest is now Nolan’s second best picture of his quarter-century career. Even as someone who genuinely loved a lot of Tenet, this is light years better.

Criticism has already likened it to the work of Oliver Stone, specifically 1991’s JFK, and you can see why. For me, Oppenheimer could well be to that political, conspiratorial epic what Steven Spielberg’s The Post now is to Alan J. Pakula’s All The President’s Men. If not a direct prequel, then certainly a thematic one, playing out the political American landscape following World War II that, in no small part, led to the choices John F. Kennedy made in office that are long speculated to have resulted in his death.

Oppenheimer isn’t as out there as JFK, justifiably so. Stone’s film (brilliant as it is) exists in a world of early 90s paranoia. Nolan’s movie is a biopic with a hefty, factual source material in Kai Bird and the late Martin J. Sherwin’s tome ‘American Prometheus’. I read it some years ago and it truly is forensic and exhaustive in examining the life of J. Robert Oppenheimer, a brilliant American physicists who, built on the theoretical work of mentors Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr, ends up through his work on quantum physics devising a blueprint for the atomic bomb. Bird and Sherwin’s book gives Nolan everything he needs to accurately depict the span of the man’s life.

It is quite staggering nobody has made a truly memorable biopic of Oppenheimer before. The man really is one of the key figures of the 20th century, and not just in the realm of science. What he ended up unlocking was transformative. His wife Kitty (Emily Blunt in the film) suggests as he is building the bomb that “the world is changing, pivoting. Reforming”. Aside from being a resonant phrase in the tumult of the early 2020s, her notion also speaks to just how powerfully the ‘bomb’ changed the future. Nolan repeatedly has characters express its importance and, by definition, the importance of Oppenheimer.

The similarity with JFK is how the core of Oppenheimer is one of assassination. Not in literal terms, but in terms of character. Following the success of the Trinity test in Los Alamos, an entire town developed for him and his cadre of scientists, and subsequent bombings of Hiroshima amd Nagasaki, forces in American politics begin turning on him. Oppenheimer goes from war hero to damaged goods lightening fast the moment he begins to express a moral quandary at the destructive power he has unleashed. Nolan’s titanic deconstruction of man’s hubris is compacted in Oppenheimer’s journey.

It feels the right moment here to point out just how magnificent two actors are throughout Oppenheimer.

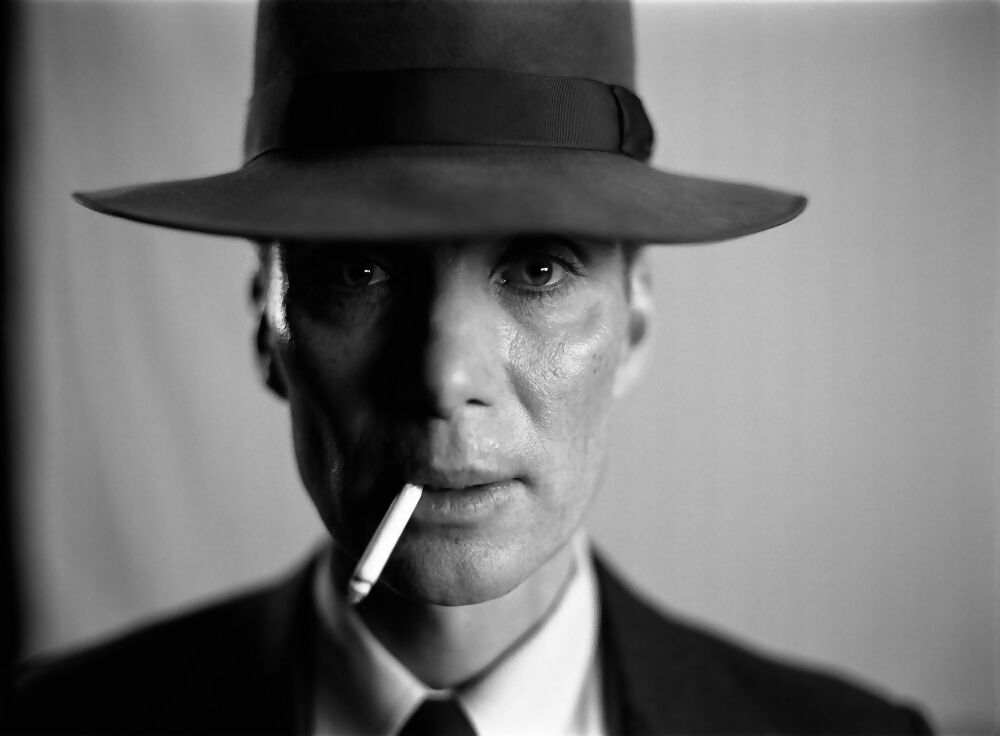

Firstly, playing the titular character, Cillian Murphy. If this doesn’t bag the Nolan film regular a Best Actor Academy Award, I can’t imagine what will. Aside from utterly looking the part, matching Oppenheimer’s gaunt, hangdog yet piercing face and physique, Murphy nails both tone of voice, physicality and the mercurial nature of the man himself. Oppenheimer might have misgivings at points about the work, but he is also a seasoned philanderer, a poor father & a suspected traitor. For all the morality surrounding the bomb, he is not a moral man and Murphy depicts that contradiction with magisterial grace. It truly is one of the greatest performances in Nolan’s filmography.

Almost on a par is Robert Downey. Jr, in the tricky role of Lewis Strauss, the Naval officer who ran the Atomic Energy Commission and whose story runs in parallel to Oppenheimer’s before they overlap. He seeks Senate approval for a role in government, in the wake of the House of Un-American Activities Commission in the early 1950s (the witch-hunt body who blacklisted suspected Communists in American society), but is haunted by a personal betrayal he feels came from Oppenheimer and schemes a complicated, legal vengeance.

Downey. Jr produces perhaps his best performance since David Fincher’s Zodiac, almost unrecognisable under thin hair and rimmed spectacles. He looks more Jeremy Irons than Tony Stark. Yet he’s magnificent in a vain, self-interested role which also encourages you to feel sympathy.

He comes into his own in the stronger half of Oppenheimer, the final 90 minutes of the hefty three hour running time (Nolan’s longest movie to date), where everything the director has fused in the first half develops into fissile material.

Nolan evokes earlier films such as The Prestige in how he plays with perceptions of narrative, employing in media res techniques to frame an exploration of Oppenheimer’s past, his youth, and his development into the man central to the atomic bomb programme. Yet this isn’t staid factual recounting. Nolan sees Oppenheimer haunted, attacked even, by visions of the awesome power he will later yield, right from the start. The Prestige comparisons continue, incidentally, in how Nolan frames his film about two men at odds, one brilliant and one vengeful, both recounting events from the future. On a structural level, even if they are very different pieces, both movies have a great deal in common.

Coupled with his traditionally bombastic sound design and Ludwig Goransson (returning after Tenet) providing a suitably volcanic score when needed, Nolan wants us to feel the heat, feel the fire, and feel Oppenheimer as a man boasting destiny. All roads lead to Trinity.

In cheeky fashion, Nolan even finds a way to have Oppenheimer voice the infamous line from the Bhagavad Gita “I am Become Death, Destroyer of Worlds”, framing it through a raucous sex scene with Florence Pugh’s mistress Jean Tatlock. The man famously never actually said that quote but it is so tied up with the myth of Oppenheimer and the nature of the bomb, losing it would have felt strange. Nolan understands the legend around Oppenheimer and chooses to subvert our expectations of those moments.

One quick sidebar to discuss Pugh and Jean, for a moment. Once again, Nolan’s apparent disinterest in female characters is clear in Oppenheimer. For all the publicity of Pugh, perhaps the hottest A-list property in recent years, joining the cast, she serves as little more than a sex object for our protagonist, spending much of her time on screen naked (Nolan employing nudity here in a way never before seen in his rather sexless earlier films, perhaps pointedly). Jean is a complex creation who deserved more.

Ditto the aforementioned Kitty, who Blunt injects with protective, put-upon gusto, but she is as sidelined often as Pugh is fridged. You sense Kitty and Oppenheimer’s relationship needed deeper exploration. Perhaps these are examples where a longer, mini-series format would have brought such characters to bear, but they do nothing for Nolan finally passing the Bechdel test.

The director is far more interested in exploring the political undercurrents beneath the creation of the bomb and how Oppenheimer ends up caught between the currents of American extremist paranoia and the fear of Soviet Communism. This becomes the cudgel with which to beat him, once he voices moral objection to his own creation, and anxiety at his own hubris. We have seen many films grapple with the American fear, post-World War II, of Soviet corruption of their democracy via their warped, Stalinist sense of Communism. What Nolan does is directly make this connective to nascent American imperialism after the war, the Truman Doctrine and the sheer, horrific aftershock of killing hundreds of thousands with such destructive power.

Where he comes down on moral equivalence is interesting. He plays the middle, suggesting that both science and politics have a part to play in Oppenheimer’s tainted history. The scientist is at paints to point out, during his FBI subpoena, that he didn’t influence policy in terms of dropping the bomb, but he is in the room when decisions are being made. He does confess his misgivings after the fact to a waspish and quietly bullish Harry Truman (a great, almost unrecognisable Gary Oldman). Who is to blame? Nolan doesn’t precisely choose, even if he makes the scheming politicians the enemy. He wants us to feel Oppenheimer’s complicity in allowing the military to exploit his science, fearful as they were of Heisenberg and the Nazis winning the first arms race. Morality is murky here. Motivations complex.

We know the story of Prometheus. We equally recall the tale of Pandora and her box. Nolan has played with Greek allusion before, during Inception, and those parallels exist here too. The director has been fascinated with the idea of brilliant men creating devices or innovations they aren’t ready for in previous films. Look at Angier’s Transformed Man in The Prestige. Take Dr. Pavel’s bomb in The Dark Knight Rises. All creations with the power to destroy.

Nolan regular Kenneth Branagh, playing Bohr, underscores this to Oppenheimer: “You are the man who gave them the power to destroy themselves. And the world is not prepared.” Einstein (Tom Conti, returning after The Dark Knight Rises) provides similar warnings. Both are men reaching out from history to decry the perversion of the centuries of scientific Enlightenment they contributed to.

I’m convinced Nolan really wants to make a horror film. He described initial concepts for Inception as such. The metronomic terror of Dunkirk frequently reached for tension building akin to being stalked by monsters. And in Oppenheimer, he goes nuclear. He fills the screen with white flashes, cosmic events, charred bodies, and in depicting the Trinity test, delivers a visual and aural template designed to terrify.

Matt Damon’s straight arrow General Groves presents all our fears before the test: “Are you saying that there’s a chance that when we push that button… we destroy the world?” What is more terrifying than the atmosphere being set ablaze and the entire planet behind wiped out by heavenly fire? Aspects of Oppenheimer are pure, apocalyptic horror territory.

There is so much more to say. For one thing, this has to be Nolan’s greatest ensemble cast ever, even for his filmography. Outside of the stellar main players, the film is chock full of great character actors, some of them only in minor roles. A particular note should be made of Jason Clarke, as Roger Robb, the FBI ‘inquisitor’ during Oppenheimer’s testimony, who is magnetic as he pushes various characters into aiding and abetting our protagonist’s disgrace. He has that junkyard dog quality of a Lee J. Cobb here. That’s just one example. It’s a remarkable assortment of stars and quality actors who truly help sell the immersion into a dark world of conspiratorial Americana.

As mentioned earlier, Goransson’s score works extremely well, as he inherits the mantle from Hans Zimmer seemingly of Nolan’s go to composer. His memorable refrain was key to the trailer, a thundering, growing mass of clashing, explosive sounds, designed to evoke the combination of atoms and particles that go into the A-bomb. They become an assault on our senses and indeed Oppenheimer’s. The moment Clarke’s character really pushes the doctor is a good example of where Goransson amps everything up to maximum before cutting swiftly to silence. From a sound design perspective, quite how Nolan’s team handles the initial moment after the bomb detonates, replacing expected explosive blowback with eerie quiet and haunting, uncertain breath, is genuinely breathtaking. It encourages us to hold ours alongside the characters, even despite knowing the outcome.

A final point on the climactic scene, a conversation teased throughout the film in typical Nolan fashion, between Oppenheimer and Einstein, a major cause of Strauss’ antipathy. The conversation itself is a sobering one but the structure of the scene entranced me more. Nolan frames Strauss walking almost menacingly toward the scientists (which we earlier saw from his perspective in a different context) implies the looming march of power & politics on the scientific community, as great minds worry about what their genius might cost the world. Nolan absolutely understands the dread he builds here, what horror again he quietly invokes, and it’s masterful.

Ultimately though, Oppenheimer is a cautionary tale character story. Murphy drives a picture filled with visual and narrative inventiveness, from repeated switching between colour and black/white palletes to those aforementioned bursts of fission. Nolan’s film feels like a warning from the past, a cinematic tinderbox reflecting our own world on the edge of what could one day be a nuclear precipice, and with technology and climate change beginning to pivot the world into an entirely new paradigm. Nolan fears one man having too much power, even a brilliant man, reinforcing his career-long obsession with the fallen genius.

J. Robert Oppenheimer never entirely escapes his legacy. Christopher Nolan’s growing fear is that neither shall we.

—

Thank you for visiting! If you’d like to support our attempts to make a non-clickbaity movie website:

Follow Film Stories on Twitter here, and on Facebook here.

Buy our Film Stories and Film Junior print magazines here.

Become a Patron here.