Are reviews a buyer’s guide, just one person’s opinion – or perhaps even obsolete? Jon Bailes argues there’s still value to thoughtful game criticism.

As a games critic, it’s both interesting and concerning to see how people talk about game reviews these days. On one hand, there is still an apparently endless fascination with how the games media judges new releases, but it’s often centred on scores. On the other hand, some people are always at pains to point out that game reviews no longer matter.

Honestly, I can understand where these sentiments come from. I might even agree that written reviews are losing relevance, although I’d argue that it’s mainly only a certain ‘traditional’ kind of review that’s struggling. And my response, as you might expect, isn’t that game reviews should be tidily buried and forgotten, but that we might reconsider what they are and what they should aim to achieve.

What do I mean by a ‘traditional’ game review, though? Well, when you look back to the first wave of professional games journalism, in the 1980s, reviews tended to be geared towards evaluating a game’s basic ‘playability’, or whether the presentation, control, difficulty and performance of a title added up to something functionally enjoyable. Considerations of visual and audio style, cunning level design and so on would filter in slowly as the tech advanced.

In contrast, the vast majority of commercial releases today are ‘playable’ almost by default. Control systems have homogenised in each genre, established design standards mean you’re much less likely to get unfairly stuck, and visuals are generally readable. At the same time, potential players can subscribe to services such as Game Pass, trying out new releases at no extra cost, or watch streamers and video reviews that show actual game footage. Aside from occasional aberrations (such as Fallout 76), then, there is less reason for the old-style consumer product review to exist.

Thankfully, I think there’s a growing understanding among critics and editors that game reviews can no longer simply be a day-one red or green flag to aid a purchasing decision. Yet we’re still a distance away from how reviews work in media like film and literature, where it’s more widely acceptable to discuss, say, the cultural relevance of a new release, how it contributes to a style or genre, or the ideas and themes it explores.

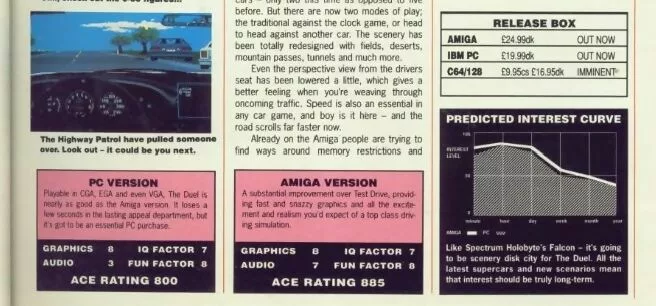

British 1980s magazine ACE had one of the most idiosyncratic ratings systems ever, with a ‘predicted interest curve’ graph and games marked out of a thousand.

If that all sounds a bit pretentious, then consider how much games have changed in the last 20 plus years. Any review of Dark Souls, for instance, will discuss its combat, level design, challenge, character builds and so on. But FromSoftware’s RPG is also riven with themes that add context to your discoveries, that bring a perverse enjoyment to its opaque design, and pull the mechanical elements into a coherent whole. Should a review not also consider what the game is about, in order to do it justice?

Indeed, a good written review is still often the most concise entryway to exploring what games are trying to do beyond the usual checklist of features. As a reader, I know I seek out critics who can introduce me to different ways of thinking about a game, and not only before I play them, but after the fact too. Some reviews are actually better read in hindsight, I believe, offering perspectives on a game world you may not have considered, or describing the experience in a way you couldn’t quite put your finger on.

With that in mind, it can also be frustrating to read the common refrain that reviews are ‘just someone’s opinion’. Of course, there’s no such thing as an objective or ‘correct’ review. Even when it comes to bugs and performance issues, different critics will find them more or less disruptive. And beyond the technical stuff, we have to weigh up with such slippery notions as art style, writing, the ‘feel’ of combat, the reward of exploration, the agency in dialogue choices, and how well these all gel together.

Still, as much as a review is an opinion, hopefully it’s a well-informed one, provided by someone who has a solid grasp of the medium’s history, genre norms, and the game’s artistic ambitions. Hopefully it’s a well-written one, explaining vividly not only if the critic likes the game or not, but why and in what ways. And hopefully it’s not ‘just’ an opinion, but an interesting one, distinctively written or unique in its viewpoint. If so, it’s the very fact that reviews are opinions that can make them worth your time.

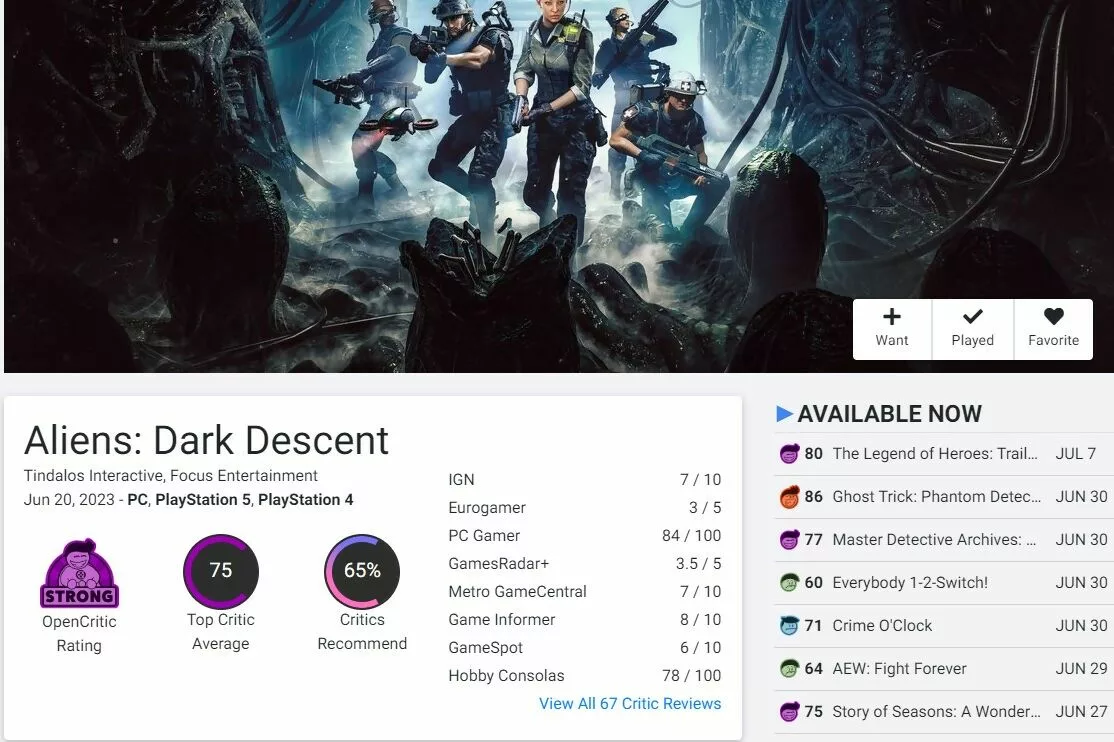

One major obstacle to more substantial criticism, however, is the other trend I mentioned at the top – the fixation on review scores. It’s easy to point to sites like Metacritic and OpenCritic as facilitators here – as much as I appreciate their efforts to collate links to reviews, the concept of a ‘meta-score’ is counterproductive. Rather than draw our focus to individual reviews, meta-scores encourage us to imagine critics as a singular entity built around a consensus, which marks those reviewers who score a game significantly higher or lower than the average as outliers.

Aggregation sites like Meta Critic and OpenCritic are useful, but also fuel an obsession with scores rather than nuance.

For an ill-informed yet vocal minority, it’s then a short leap to conclude either that such critics didn’t ‘get’ the game, or they overlooked its flaws. This is no small matter, especially since outlier reviews can attract waves of online abuse (as a white man, I receive a tiny fraction of this compared to many women and minority group members among my peers). Of course, such reactions reveal a complete misunderstanding of how reviews work – reviewers play upcoming releases in a bubble, oblivious to what scores other reviewers will give, so they have no idea what the consensus will be before publication. But ignorant treatment of outliers can mean that some of the most considered and deeply informative reviews are unfairly dismissed, when their value lies precisely in offering an alternate view.

I have nothing against review scores, personally. I review games on five-point scales, ten-point scales, percentages scale and with no scores at all, and have no real preference. But while I think scores can be a useful way to sum up a critique, it’s important to acknowledge that they don’t mean much on their own. For example, a lot of people tend to assume that a three-star game is bad and a four-star game is good, but what if the reviewer was on the fence and ultimately just had made a call one way or the other? Only by reading the intent behind the score can you get to grips with their experience.

It’s not only aggregators and players that make too much of scores, either, but games media and publishers themselves. Historically, many magazines went as far as to rate even individual elements of games such as graphics and ‘lastability’, in some cases adding them up to a total like some scientific formula. There’s still something of a hangover from those days, I think, viewing games as measurable in some sense. But even beyond that, some sites still promote scores as the key talking point of their reviews, rather than, say, quotes from the text.

Game publishers, meanwhile, giddily splash review scores across advertising, while developers may be incentivised to aim for certain meta-score targets. The way the review process works also implies (unsurprisingly) that publishers have little interest in generating interesting critique rather than friendly digits. Plenty of review codes are sent out less than a week before review embargos, and since many sites need to publish as soon as the embargo lifts, reviewers are forced to rush through big games and write about their experience with no time to digest and reflect.

Is this system sustainable? If players do increasingly turn away from traditional reviews, then perhaps not, no matter how much the hype cycle pumps up the numbers. I’d prefer it then if we evolved together, asking what games reviews are really for today, and how they can contribute to richer engagement with the medium. As a critic, I just hope I can practice what I preach.