How do you follow the huge success of Star Trek II: The Wrath Of Khan? Well, by undoing some if works. Spoilers ahead for The Search For Spock…

If director Nicholas Meyer laid the template for the tone and style of an entire generation of the franchise to come with Star Trek II: The Wrath Of Khan, Leonard Nimoy’s Star Trek III: The Search For Spock cements what Star Trek on the big screen would go on to be.

By 1984, the ‘New Hollywood’ movement which drove American cinema during the 1970s had well and truly given way to the blockbuster era. Star Wars had come and gone with two successful sequels that cemented the idea of fandom and popular culture. Indiana Jones was born and onto his second movie in Temple Of Doom. Eighties pop had subsumed 70s disco and early 80s punk. Reagan-era America was all about brands and colour and money and merchandise, offset by resurgent 1950s-style conservatism.

The Star Trek franchise, as it was by now becoming, was being born into a very different ecosystem compared to The Motion Picture, and its difficult delivery in a depressed, paranoid 1970s.

The Motion Picture sought to capitalise on Star Wars’ wonder by using Kubrick-esque grandeur, but Meyer understood that ship had already sailed. The Wrath Of Khan existed in a limbo space between the old and new. Meyer had his own, auteur vision for Gene Roddenberry’s universe, bringing forth the nautical, Hornblower stylistics that Roddenberry himself drew inspiration from in the 1960s.

Meyer also understood, however, that people wanted adventure and excitement as the 1980s turned. In taking the bones of numerous scripts that posited a return of Khan Noonien Singh, that Star Trek needed the kind of supervillain antagonist that had so wowed audiences in Star Wars. He also, equally, still believed a story should remain told. When Paramount, aware The Wrath Of Khan had done well on a much smaller budget than The Motion Picture, decided to continue the voyage, and decided that Star Trek just wasn’t Star Trek without Spock, Meyer firmly resisted their overtures to come back and continue the adventure.

He told the Boston Globe some years later:

I thought then that canceling Spock’s death was an unmitigated disaster. For one thing, it was driven only by crass commercial considerations. But beyond that, it was a dry hustle of people’s emotions, to wring the tears out of them — and test audiences literally sobbed at Spock’s death — and then say, ‘Forget it, folks, just yankin’ your chain.’

Was he right? You be the judge.

Spock’s death is not simply the most iconic moment in Star Trek history, it ranks up there in the annals of cinema. In an age of intellectual property mining where no popular character remains off screen for long, the idea of permanently killing a figure like Spock, and in such a sudden, sacrificial manner, would be unconscionable.

Yet his demise meant something, balancing out the threat posed by Khan, and leaving a rejuvenated Kirk with a bittersweet ending. It took Spock’s death to give Star Trek and its middle-aged crew a new lease of life, at least in Meyer’s eyes.

Not so Paramount.

With Spock’s body committed to the Genesis planet, a scene added to keep the door open, the possibility remained for Star Trek’s legendary Vulcan to return. Nimoy was keen to keep playing the character after The Wrath Of Khan, in a marked turnaround from the mid-1970s, and Paramount soon offered him the opportunity to direct, paving the way later for Star Trek actors William Shatner and Jonathan Frakes to take up the mantle in future films.

Nimoy and producer Harve Bennett, with Roddenberry hovering in the background as a ‘creative consultant’, set about building a story around Spock’s literal, Christ-like rebirth juxtaposed with the failure of the Genesis planet, created after Khan’s super weapon detonated, only to reveal the hubris of man’s attempt to play God.

With Nimoy predominately off screen for this third adventure, it meant a somewhat different dynamic to Kirk’s interaction with his crew. He limps the Enterprise back to Earth after battling Khan, alive but somewhat broken by Spock’s death, nor can he turn to Leonard McCoy (DeForest Kelley) to help ease his anxieties.

In another wink toward Spock’s potential revival at the end of the previous film, McCoy unexpectedly becomes host to Spock’s ‘kat’ra’, his “living spirit”, which becomes enmeshed with Bones’ gruff cynicism as he retreats into himself. Kirk finds him brooding inside Spock’s old Enterprise quarters, grappling with the cold, green-blooded Vulcan logic his rugged, feeling physician so often found maddening.

“Only his body was in death, Kirk!” Spock’s father Sarek tells him, rebuking him for Kirk not being aware of the (heretofore unmentioned) Vulcan ability to preserve their soul in the minds of others (this is seldom also mentioned subsequently, perhaps given how profound a concept it is).

The idea is, undeniably, a cheat allowing for Spock’s return, an early popular culture example of a corporate entity being conscious of the effect on a paid-up fandom of a beloved character. Spock’s revival here moves from feral ‘Neanderthal’ boy via gawky teenager all the way back to a ‘reset’ of Spock’s factory settings to the purely logical figure he was seeking to become in The Motion Picture. More on that later.

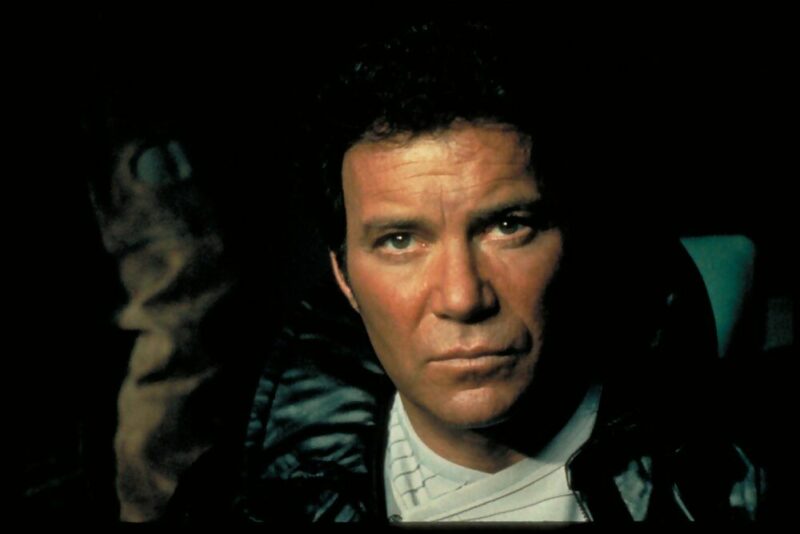

Though focused around the ‘search’ for Spock, Nimoy’s film is principally nonetheless about Kirk. After The Wrath Of Khan revived him spiritually, The Search For Spock reverts also Kirk back to his 1960s factory settings. The stark, distant Admiral Kirk figure from The Motion Picture is a world away from Shatner channeling the swaggering, cocky, rule-breaking cowboy he played in The Original Series.

Placing Spock’s life above all else – especially his career – Kirk becomes singularly minded in stealing the Enterprise to save his friend. “You do this, you’ll never sit in the Captain’s chair again,” he’s warned by Captain Styles (James B. Sikking), such an embodiment of the marshal Starfleet naval structure Meyer introduced that he wields a cane.

We know, ultimately, that this won’t be true, so we cheer Kirk on. Even when he was promoted to Admiral, he was still ‘Captain Kirk’. By now, the legend of that persona outstrips the man, both in the world of Starfleet and the Federation, and beyond Star Trek itself, so of course he would engage his loyal old crew to steal their ship to save their friend.

It is a pure tale, clued into The Search for Spock’s pulpier intentions. It wants to be a big-budget, rambunctious family adventure with heroes and villains. It’s why the legacy of Khan, Genesis, or officious Starfleet officers and their big sleek starships such as the USS Excelsior (that bucket o’bolts!) aren’t enough.

The Klingons are thrown in for good measure, properly returning for the first time (after briefly popping up in The Motion Picture) since the 1960s.

Credit to The Search For Spock in this regard, because Commander Kruge is a genuinely vicious brute. A year before Christopher Lloyd would become an icon himself as Doc Brown in Back To The Future, he essays Kruge as a gruff, boorish and nasty Klingon opportunist who kills his own men and, in a moment that cements him as one of Star Trek’s more underrated and potent villains, orders the savage murder of David Marcus (Merritt Butrick), the adult son Kirk reunited with in The Wrath Of Khan.

It’s a genuine shocker, brutally rendered, and affords Shatner possibly his greatest moment of acting in the entire franchise. The way he delivers “you Klingon bastards, you killed my son,” as he falls to the floor of his bridge is heartbreaking. I’d point to that moment if Shatner is ever accused of not being a good actor.

It gives The Search For Spock a true sense of consequence, around all of the fun and frothy moments the film provides (the Enterprise stealing sequence, for instance, with moments such as Nichelle Nichols’ Uhura locking a smitten young officer in a closet).

Nimoy’s film genuinely takes risks. It becomes the first of three Star Trek movies to destroy the Enterprise (and to date it’s never been bettered), removing just as iconic a feature of Star Trek as Kirk and his crew. “My God, Bones… what have I done?” Kirk says, watching the hauntingly beautiful sight of the ship wreckage enter the Genesis atmosphere. “What you had to do.” Bones tells him.

The destruction of the Enterprise, the death of David even, are part of what The Search For Spock is about: sacrifice.

On a broader level, Star Trek understands in order to bring back the character most beloved in the entire saga, it has to make a trade. It has to sacrifice what the series was on the small screen for what it becomes on the big screen. The Search For Spock changes the direction of the movies during this era forever. They will always, bar one exception when Meyer later returns, be designed as high concept, blockbuster events. There will almost always be a Kruge, as there was a Khan. Star Trek on a cinema screen will be an entity separate from what The Next Generation, in three short years, will be on television.

The final scenes really bring this home. In a grand sequence, scored majestically by James Horner (in his last of two incredible scores for the series), Spock’s kat’ra is returned to his new, Genesis created body, overseen by screen legend Dame Judith Anderson (in one of her final roles), as Kirk, Scotty, Chekov, Sulu and Uhura – all of whom having potentially thrown their careers away – watch on.

Spock is alive. Yet he at first seems distant. Does he know them? Does he remember them? Spock begins to recall the final lines he said as he ‘died’ in The Wrath Of Khan. “Jim… your name is Jim.” Kirk, and we, are overcome with emotion. The Spock we loved is still there. Our friend has returned and this is the point – Spock, Kirk and all of them, are now bigger than the story they’re in. The franchise enters a new phase of existence at this moment.

Sarek, mournfully, acknowledges what this cost Kirk – his ship, his son. “If I hadn’t tried, the cost would have been my soul,” he replies.

That’s the core of The Search for Spock. It becomes the search for Star Trek’s soul.