Is Tetris a critique of Communism, a parody of Reaganomics, or an embodiment of the Holy Trinity? Steven examines the puzzler’s multiple, very strange interpretations.

At July’s UK National Film Awards, the trophy for Best Actor went to Taron Egerton for his role in Apple TV’s Tetris movie, which also won Best Drama. That there’s a movie at all may have surprised some people watching: how can you strain a narrative out of a famously abstract 8-bit puzzle-game?

An abortive, earlier answer to this question was provided by Larry Kasanoff, producer of the ‘classic’ 1995 Mortal Kombat movie, who in the mid-2010s repeatedly claimed to be about to transform the puzzler into an epic sci-fi trilogy with an all-Chinese cast. Kasanoff promised not to fill his film with anthropomorphic extraterrestrial blocks with feet running around and kicking primitive earthlings to death across central Beijing, but that was precisely what some of us would like to have seen.

Apple TV’s own, more successful dramatic solution was to focus on the famously complex business history of the game. But numerous other persons down the years have sought to add their subjective personal narratives to the title too, with Tetris becoming a handy Rorschach ink-blot test for those addicted to overthinking even the simplest pleasures in life.

Credit: Apple TV.

The Soviet block

Designed by computer engineer Alexey Pajitnov while working for an offshoot of the Soviet Academy of Sciences in 1984, Tetris was the first real piece of entertainment software licensed for export outside the USSR. As such, it was jokingly marketed to US consumers as a Cold War Trojan Horse, intended to reduce western productivity as American office employees wasted their time rotating blocks instead of doing any real work, thus allowing the Commies to pull ahead economically.

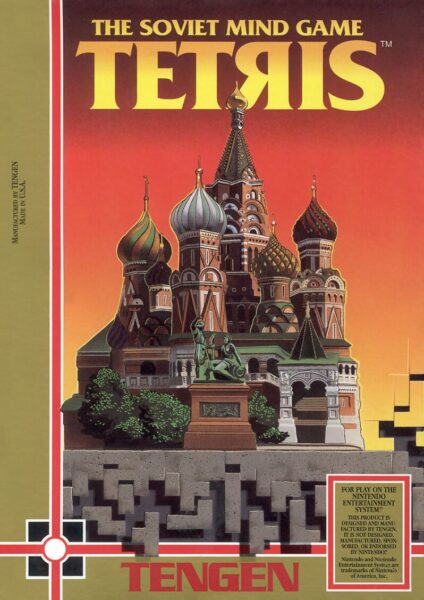

Tetris: The Soviet Challenge was the title given to the game when it was released by publishers Spectrum HoloByte on western computers in 1988. Adverts ran with the tag-line, ‘The Cold War Is Over. Almost…’ and promotional copy like “Just when East/West tensions are beginning to ease, the Soviets have scored a direct hit on the US.”

The Amiga version’s play area was surrounded by stereotypical pixelated images of Soviet life, like floating cosmonauts and humble citizens riding horses, and when you achieved a high-score, you were ranked as one of the ‘Top Ten Comrades’.

The most famous version of Tetris, released on the Game Boy in 1989, came with the James Bond-aping slogan ‘From Russia with fun!’ on the cover, had the famed onion domes of Moscow’s St Basil’s Cathedral on the title-screen, and played a chip-tune version of the traditional – and indecently catchy – Russian folk-song Korobeiniki on a constant loop during play.

Therefore, Tetris has often been seen either as a piece of subliminal Russian propaganda critiquing capitalism, or else an even more daring piece of internal Soviet criticism of the ruling regime itself. There’s a (surprisingly good) song now making this argument, sung by “the man who arranges the blocks”.

Just another brick in the (Berlin) Wall?

Online, it’s easy to find players making semi-humorous political interpretations of the game like this:

“You, aka the central planner, must cram as many differently shaped and coloured pieces into the same rigid box as you can … all serve a purpose under Bolshevism, and you achieve points by maximising harmony (aka creating lines). And when you do so, the threat of systemic collapse is reduced a little bit … At first, central planning is easy, even rewarding … but as time passes, you get pieces which simply will not fit right … Holes start to appear in the façade … Eventually, the jumble of pieces is near breaking point, and you start attempting wild strategies to stave off the impending revolution, but it is for naught … you cannot win; like a Soviet peasant, you simply avoid death for as long as possible.”

Therefore, it appears Tetris accurately predicted the fall of the Berlin Wall – at least if you believe the above web-joke. The trouble is, there are some Tetris ‘scholars’ out there whose interpretations are intended to be taken seriously.

The most famous over-reading of Tetris appeared in leading media studies academic Janet H. Murray’s 1997 book Hamlet on the Holodeck, which sought to explore the then-emerging new world of video game narratives.

Murray read Tetris as a symbolic drama which trapped players in a microcosmic representation of post-Reaganite free-market capitalism. In it, semi-enslaved worker-drones repeatedly performed meaningless tasks, none of which would ever ultimately be finished, like painting the Forth Bridge. Every day, depressed Dilbert-like employees and gamers alike must perpetually “clear off our desks in order to make room for the next onslaught” of tasks or bricks, the game thus becoming “a kind of rain-dance for the postmodern psyche, meant to allow us to enact control over things outside our power,” Murray wrote.

Some other, less grandiloquent critics disagreed, with a rift opening up between ‘narratologists’ like Murray, and ‘ludologists’, who argued that sometimes games were just – well, games. One such sceptic was Markku Eskelinen, who, considering he describes himself as “an independent scholar and experimental writer of ergodic prose, interactive drama, critical essays and cybertext fiction”, as well as “easily the most iconoclastic figure on the Finnish literary scene”, you may have expected to be on Murray’s chin-stroking side – but no.

In his dissenting 2010 essay ‘The Gaming Situation’, Eskelinen also discussed “The Phenomenology of Tetris”, dismissing over-readings like those of Murray as pseudish nonsense. He said viewing Tetris as a Communist critique of capitalism would be as stupid as viewing chess as a metaphor for racial inequality (interestingly, there are people who do think this).

Ultimately, Eskelinen concluded that Murray’s reading was mere “interpretive violence”. Unfortunately, there’s a lot of it about.

Tetris – the puzzler that sold several million Game Boys. Credit: Nintendo.

The Tower of Babble

It is almost as if there is some kind of competition going on to see who can come up with the daftest way of wildly misperceiving Tetris. One online joker writes that, as the Soviet Union was an officially atheistic regime, the game was actually conceived as a mockery of religion.

The word ‘Tetris’ comes from the Greek ‘tetra’, meaning ‘four’, as each falling shape in the game is made of four blocks. Therefore, says the web-satirist, the game is a blasphemous representation of the ‘fourth hypostasis’, an addition to the Christian Holy Trinity of Father, Son and Holy Spirit – the fourth hypostasis being the Communist State. (Someone online has actually found an apparently genuine decorative image resembling a Tetris block carved on a Russian Orthodox cross, but this is surely just a coincidence.)

Jokes these days often have a habit of becoming reality. A real online paper of academic game-design theory, ‘No Truth in Game Design: An Argument For Idolatry’ by writer Jason Johnson, explains how, once a game designer has released their work to the public, “he relinquishes all control of said game to the player” thereby allowing them to interpret it however they want: even completely unreasonably.

Tetris itself is particularly susceptible to multiple readings, Johnson says, as “its abstractness allows its structure to be easily accessed and dissected. The transparency of its landscape, lacking any visual representation of the outside world, frees the mind to [consideration of] incorporeal things.”

This frees Johnson to imagine the game as a religious metaphor about the people of the Bible building the Tower of Babel, a hubristic attempt to construct a tower up to heaven, before, in the end, it all inevitably comes crashing down before their eyes, just like a failed session of Tetris.

St Basil’s Cathedral was a familiar sight on 1980s and early 90s Tetris boxes.

Yet Johnson also perceives the game as a holy trinity of puzzle-gaming elements: infinity (as, theoretically, it could be played forever by a perfect player), difficulty and randomness. It’s a trinity Johnson represents by drawing a labelled triangle. “God is composed of three entities [Father, Son, Holy Spirit], all of which are one, and at the same time separate.” A Trinity is often represented symbolically as a triangle, just like Johnson draws Tetris as being.

Is Tetris the fourth hypostasis of God after all? Maybe, although Johnson adds, “In fact, our Trinity compares more favourably to the Hindi Trimurti, in which Brahma the One who Creates would be analogous to randomisation, Vishnu the One who Maintains, to infinity, and Shiva the One who Destroys, to the increasing difficulty scale.”

Elsewhere in the same essay, Johnson subjects the title character of Nintendo’s 1981 Game & Watch outing, Octopus, to a sub-Nietzschean reading in which the supposed octo-god “encourages players to will themselves to power” just like Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment. Eventually, they become “caught in the tentacles of a gargantuan God, foiled in their attempt to steal away the sacred knowledge that it guards” and die.

Which is funny, because I thought Octopus was just a handheld LCD game about a deep-sea diver trying to avoid getting fatally whacked in the head by the arms of a big sea-monster.

The writing’s on the wall

None of the above acts of “interpretative violence” were ever the intention of Tetris’ original designer, Alexey Pajitnov, who sought simply to create something fun amid the unpleasant greyness of 1980s Marxism-Leninism. But no matter. At the mercy of quasi-academic writers, we increasingly inhabit a world in which everything in existence must now be relentlessly over-interpreted as wildly as possible – including harmless 80s puzzle games.

Larry Kasanoff’s old idea about transforming Tetris into a thrilling sci-fi trilogy suddenly seems altogether more appealing – and more rational.